By Kim McDarison

Seated in his Fort Atkinson home of 31 years, Fort Atkinson native, Dick Schultz, has many memories to share.

As Veterans Day approached, he turned his thoughts to his time spend in military service. As an enlisted man in the U.S. Army, he signed up for three years, half of which were spent in Vietnam, and half were served stateside.

Seated with “Hyacinth,” a 7-year-old Chihuahua-rat terrier mix, by his side, he smiled as he revealed that, while he had taken many trips into the field while serving in Pleiku and An Khe, he didn’t think of himself as brave.

“I went out so many times I got an Army Commendation Metal for going above and beyond. I didn’t think it was courage. I found out after the service that I have ADD (attention deficit disorder),” he said, adding that when sitting in camp, “the routine wore on me, so I liked going out into the field.”

As an Army soldier assigned to military intelligence, he said, while in Vietnam, some of his time was spent receiving information from field agents who would report the whereabouts of communist targets, including politicians and leaders. Schultz said his job was to track such individuals, watching their movements while looking for patterns. He’d record their movements on a map, and when the timing seemed right, he would go out into the field in search of his targets.

When in the field, he said, he was responsible for carrying military documents, which included a list of targets. Soldiers would go into Vietnamese villages, secure the area, and then Schultz would come in with his list, looking to match names with those people residing in the village.

Schultz described a system whereby soldiers would divide villagers into groups and ask them about the names of people with whom they had contact.

“If they all said the same names, that was good,” Schultz said, but if they gave different names, he said, “then we would say: ‘you’re coming with us.’”

In the field, as he waited, sometimes during the night, while a platoon secured a village, he would find himself waiting and sleeping in fox holes, which, he said, were like small trenches, maybe 2-feet deep and six-feet long.

The space was just enough for soldiers to keep their heads below ground, he said. During one such occasion, he recalled, a mortar exploded mere yards from his head. The experience left him shaken and temporarily without hearing, he said.

It was a dramatic change from what he was used to: twelve years earlier, he was a boy in Fort Atkinson, where he spent his time fishing, and helping his dad, Ralph, deliver milk.

A native of Fort

Schultz’s earliest recollections begin with the military: Ralph was a World War II veteran, he said. After the war, the family arrived in Fort Atkinson. Schultz was born while the family lived in temporary housing which was erected in Jones Park.

It was the late 1940s, Schultz recalled, and in Fort Atkinson, there was a housing shortage.

Sometime around his fifth birthday, Schultz, said, the family moved to a home on Robert Street. In all, the family would grow to include five children. Schultz is the third child born to Ralph and his wife, Ruth.

Recalling Fort Atkinson in those earlier years, Schultz said Ralph worked for Healthway Dairy and Ruth worked as an accountant, first for the James Manufacturing Company, which carried the Jamesway line of dairy and livestock equipment, and then for W.D. Hoard.

At 7 or 8, Schultz said, he would accompany his father on his milk delivery route, but by the time Schultz was in junior high school, he said, his father’s health prevented him from continuing in that work. Instead, Schultz said, his father became the first full-time manager of the Dugout, an American Legion tavern which continues to operate today.

With Ralph serving as tavern manager, Schultz said he continued to help his father. He would collect discarded bottles and sort them into large barrels so that a bottle deposit could be collected. He did that work mostly on weekends and over the summer, he said, and after helping his father, he’d find his way to a favorite spot along the Rock River and go fishing.

Forty years later, Schultz recalled, a fishing ban was enacted which included his spot.

“Fishing in the Rock River was part of my culture. I was angry about that; that’s why I ran for city council,” Schultz said. When he won the seat, in 2009, one of his first acts was repealing the fishing ban, he said. Schultz served as a Fort Atkinson City Council member until 2015, when he decided against seeking another term. His seat was filled by Councilman Mason Becker, who is today serving his fourth term.

A fire at J.C. Penny

In 1966, Schultz said, he was hired part-time at the Fort Atkinson J.C. Penny. The store was located on Main Street where The Bridge is today. After he graduated from Fort Atkinson High School, in 1967, the company wanted to employ him full-time and placed him in a store in Watertown. A few months later, he said, he was able to secure full-time work at the store in Fort.

Describing the downtown area in Fort Atkinson, Schultz said: “In those years, there were lots of big retail stores. We had a Penny’s, Sears, Montgomery Ward, all on Main Street. We had Schultz Brothers, which was a dime store — no relation — and a Ben Franklin.

“Everybody was open on Friday night until 9 p.m., and on Saturday, we had lots of sales. Nobody was open on Sunday.”

In late 1968, sometime after Christmas, Schultz recalled, J.C. Penny had a fire. It damaged much of the building, he said, but left some of the store’s merchandise untouched.

Schultz stayed with the company long enough to help with a fire sale, held at what was then the former Montgomery Ward building, and then, able to collect unemployment, he moved into the YMCA in Madison and volunteered with the 1969 Robert “Toby” Reynolds mayoral campaign.

Two and a half months later, Schultz said, he enlisted into the U.S. Army.

Back then, he said, he supported the war. “I was even passionate about it,” he said.

Schultz enlisted in January of 1969, but he took a delayed enlistment, he said, thinking he could avoid attending bootcamp during the winter months.

Before he enlisted, Schultz said, the Army had planned to draft him, but he failed his physical because he was overweight. He wanted to serve, he said, adding “I thought I had a responsibility to serve,” so he lost weight and then chose to enlist.

Schultz noted that soldiers who were drafted into the Army were expected to serve for two years, but those who enlisted were signed up for three. As an enlisted soldier, one could choose a course of specialization. The chosen spot would be made available to that soldier once basic training was completed and they passed any required exams, as long as a space was available.

Schultz selected military intelligence, he said, because it sounded interesting.

In April of 1969, at the age of 20, Schultz was sent to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he completed basic training, followed by Advanced Individual Training (AIT) at Fort Holabird in Maryland, where he was trained in military intelligence, also known as MI.

“In MI school I learned how to read and chart maps. It was a lot of working with agent reports from agents in the field,” he said, adding that part of the job required developing an understanding of various field agents’ ability to be accurate.

“To make reports, you had to understand grid coordinates,” he said.

A year in Vietnam

Schutlz arrived in Vietnam on Oct. 1, 1969.

The trip required boarding a commercial airplane with many other servicemen, leaving from Seattle, Wash., and arriving in Long Binh, a military staging area near Saigon.

He was assigned to Camp Enari, a large base camp in Pleiku as part of the 4th Infantry Division. Three months later, he was moved to An Khe, a camp in the country’s mountainous region.

Schultz said he arrived in Vietnam as a private first class, and moved through the ranks of E-2 and E-4, which, he said, was the Army’s equivalent of a non-commissioned corporal.

Describing activities in and around An Khe, Schultz said, on some days, he might go on a mission with a “Snoopy” pilot, describing the craft as a “little birddog plane.” The Snoopy, which had a bulletproof bottom, was used as a decoy. As it flew noisily behind the clouds, the enemy would fire on it. The little plane would be followed by a larger one, a Huey Cobra Scorpion, which would surprise the enemy and “take them out,” Schultz said.

There were occasions when the Snoopy would come back shot full of holes, he said.

While in Vietnam, Schultz said, he made it his special mission to find a Montagnard, a term used to describe various indigenous people living in the Central Highlands, named “Glor.”

According to Schultz, Glor would go into Vietnamese villages, accuse people of talking with American soldiers and then shoot them. It was a scare-tactic he used to keep people from talking with the soldiers, Schultz said, and he often shot innocent villagers just to make a point.

Tracking Glor and his platoon using agent reports and maps, Schultz began to see a pattern in the Montagnard’s movements, he said, and sent platoons out to find him. The first three or four missions were unsuccessful, but then, there was success.

Both Glor and his second-in-command, “Mon,” along with many in their platoon, were taken out by American soldiers, Schultz said.

Further describing the work, Schultz said: “As a military intelligence officer I had to carry the documents. I had to sleep with classified documents. I had a list, called the list of communist offenders. I was in the Viet Cong Infrastructure (VCI). I was in the Order of Battle section. Our job was to determine where is the enemy, where are their troops. My job was to target the politicians and leaders.”

After serving for about a year in Vietnam, Schultz said, he was shipped back to the United States, but he still had another year and a half to serve in the military. he was sent to Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

“It’s also important to understand I came back opposed to the war,” Schultz said.

While in Vietnam, over time, he said, he developed a sense that the country was engaged in a civil war and Americans were dying for what he came to see, he said, “as no good reason. I was asking myself: ‘Why are we here?’”

Before he went to Vietnam, Schultz said: “I believed the war needed to be fought to control the spread of communism.”

Describing his thoughts a year later, he said: “It was a government not wanting to lose control, and the people were not on our side. They were sick and tired of Americans and North Viet Cong. Both sides just wanted it over. You can’t win a war if people are not on your side.

“It looked senseless. We were losing American lives for nothing.”

Back in America

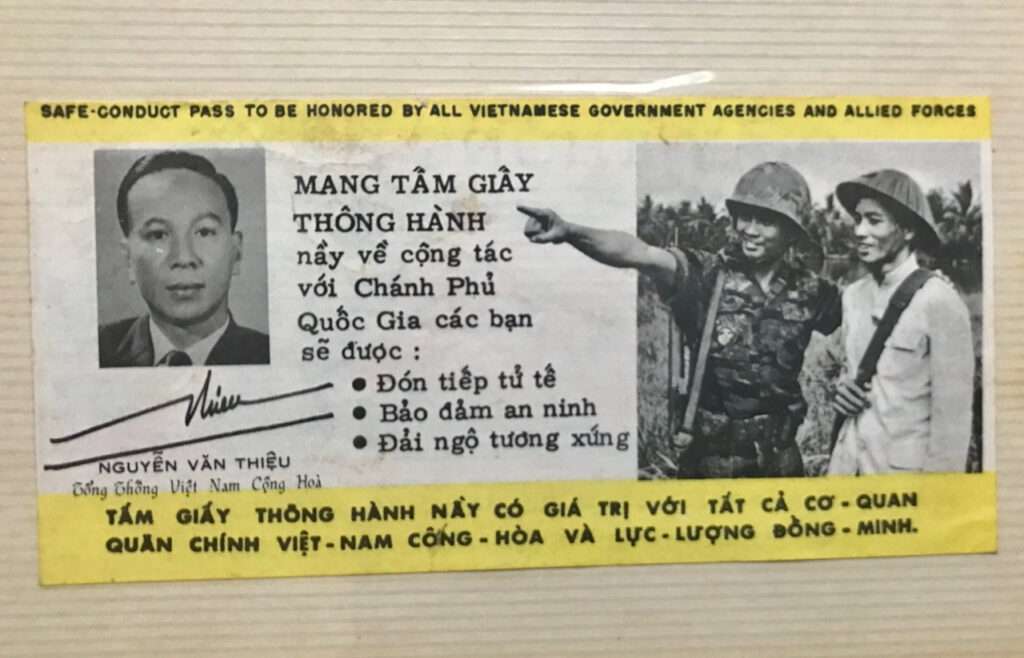

In America and stationed at Fort Bragg, Schultz said he was in the 15th Psychological Operations Battalion, attached to the John F. Kennedy Center, which was attached to the Green Berets.

Psychological Operations might include making leaflets to drop by plane in communist Vietnam, telling people they were on the losing side and asking them to surrender. The enemy did the same thing, Schultz said.

As an operations sergeant, he said, he spent much of his time maintaining records, making work assignments, and assigning rooms to incoming soldiers arriving at the base.

He was “Sergeant Schultz,” he said, and, he quipped, like the character, “I see nothing.”

A return to Fort Atkinson

After three years in the military, Schultz returned to Fort Atkinson, where, he said, he found things “pretty much the same” as he’d left them.

In 1972, he said, he ran for a seat on the State Legislature.

The late Byron Wackett, then the state representative of the 39th District and a Republican from Watertown, was running for reelection.

Schultz ran against Wackett and lost, he said, but during the campaign, the two became friends.

“Politics back then were different. People’s attitudes were different, too. Now if you don’t think the same way, you’re stupid,” Schultz said.

After returning from Vietnam, Schultz said, he lived in several homes in Fort Atkinson before moving into the home where he lives today.

In 1972, he began working at Copps Department Store, which was located in what is today the former Shopko store. The building is being developed into indoor storage units.

Active in local government, Schultz served over the years on the Fort Atkinson City Council, the School District of Fort Atkinson Board of Education, and is today a member of the Jefferson County Board of Supervisors. He also is a member of the Fort Atkinson Beautification Council.

Additionally, he has provided a home to numerous students attending Fort Atkinson High School through the district’s foreign exchange program. Photos of his students fill his living room walls. Schultz began hosting students in 1991 and continued until the 2019-2020 academic year.

Over the years, his devotion to Fort Atkinson has remained constant.

“It’s a friendly place,” he said.

Seated on his couch with 7-year-old “Hyacinth” a chihuahua and rat terrier mix, Dick Schultz shares stories about his time in Vietnam and his life in Fort Atkinson. He holds a “veteran’s quilt” presented to him in 2020. The quilt was made by members of a Deerfield-based quilting guild, called “The Prairie Piecers” in honor of his military service. Kim McDarison photo.

A 20-year-old Dick Schultz is pictured in his “hootch,” defined as a soldier’s living quarters in Vietnam. Schultz arrived in Vietnam in October of 1969. The photo was taken shortly after his arrival. Photo contributed by Dick Schultz.

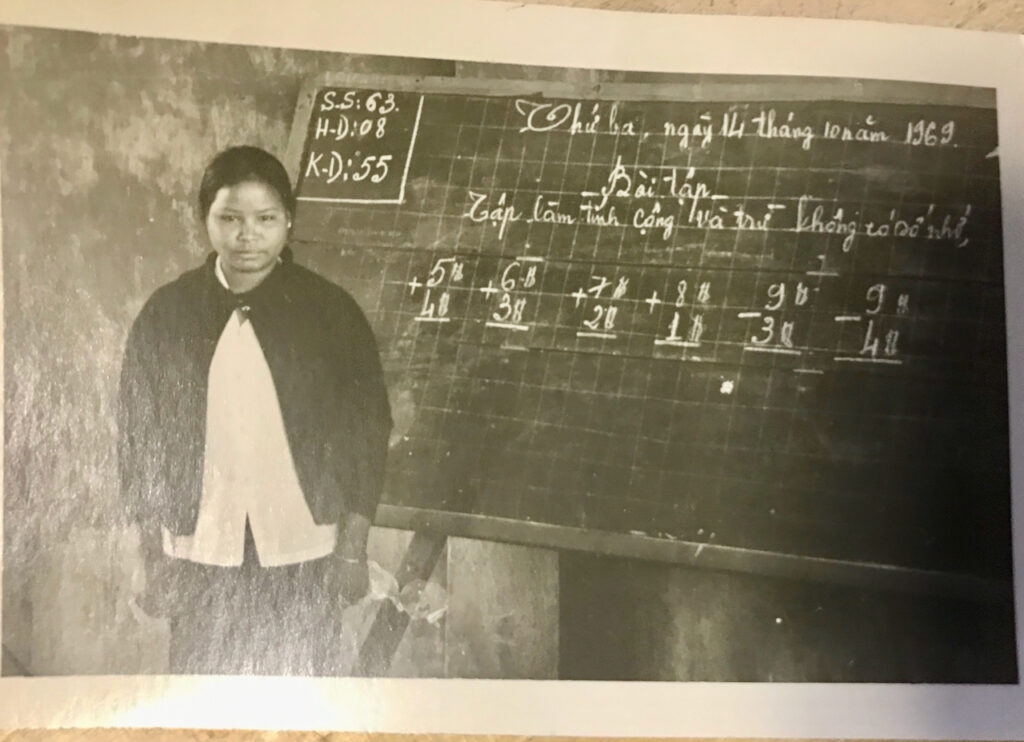

A photo of a Montagnard school teacher as shared by Dick Schultz.

Two photos above: Examples of psychological operations leaflets that were dropped by American planes inside communist Vietnam. Photos courtesy of Dick Schultz.

This post has already been read 4859 times!