By Kim McDarison

The City of Fort Atkinson has recently purchased the former Loeb-Lorman site and plans are underway to prepare it for new uses. Although dormant, the property has a compelling history, including its former and longtime use as a scrapyard, coupled with the lives of the immigrant family which worked to create it.

According to Barbara Lorman, who arrived in Fort Atkinson from Madison shortly after she married her husband, Milton, in 1953, the Lorman family history, leading to the establishment of the scrapyard, began sometime before 1913, when her father-in-law, Louis, emigrated from Russia into the United States.

Arriving in America and Fort Atkinson

Like many American immigrants, Barbara said, Louis arrived in New York City, and, hoping to stay with relatives, he journeyed to Wisconsin, arriving in Milwaukee. Relatives in Milwaukee suggested he continue moving west to Fort Atkinson, a community which grew from a military fort and stockade developed during the Black Hawk War of 1832, and continued to grow during the mid-19th century as pioneers, often migrating from New York state, according to online historical accounts, arrived into the area.

Recalling the family history, Barbara said she remembered being told that her father-in-law settled in Fort Atkinson after learning he had a widowed aunt, who had a married daughter, and the daughter had a large family with many children, living in the community.

Piecing the story together from memory, Barbara said she believed her father-in-law was likely no more than 20 when he arrived in Fort Atkinson. A Russian emigrant, she said, the family was Jewish, and in those days, in Russia, the tsar was still in power.

According to online historical accounts, the House of Romanov held power in Russia between 1613 and 1917. The dynasty ended in 1917, during the Russian Revolution, which concluded in 1923, placing the Bolsheviks in power. Tsar Nicholas II was in power when his family’s dynasty ended.

In those years, in Russia, Barbara said: “Once you were 18, if you were a boy, you were sent to be in his (the tsar’s) army. If you were a Jewish boy in the army, most understood that you would never be seen again.”

Many young men fled the country before they turned 18, she added.

Louis left to avoid that fate, Barbara said, adding, by the time he arrived in Fort Atkinson, his thoughts likely had turned to earning some money.

When he arrived in New York, he didn’t speak English.

When he arrived in Fort Atkinson, Barbara said, she believed he found a room, opting against living with his relatives.

Barbara recalled that his Fort Atkinson relatives’ surname was Weinberg.

Many of the Weinberg children graduated from Fort Atkinson High School, she said.

A recent story appearing in the Whitewater Banner, follows members of the Weinberg family, some of whom, according to the Banner’s story, began a scrapyard in Whitewater. Signage detailing some of that history was recently erected in Cravath Lakefront Park. The Banner’s story can be found here: https://whitewaterbanner.com/new-historical-sign-at-cravath-lakefront-park/.

Ultimately, Barbara said, some of the members of the Weinberg family made the decision to leave Fort Atkinson and move to Chicago.

Upon his arrival, Barbara said, Louis, whom she described as “a pretty friendly man,” began looking to build roots in the community.

He liked chickens, Barbara said, adding that she believed he might have raised chickens before he found a friend who loaned him $28 to buy a horse and a wagon.

Back then, Barbara added, people starting off with wagons typically became peddlers.

Louis, she said, “was probably going from farm to farm, offering some kind of service. The horse and wagon gave him a start and he began to earn and save some money.”

Barbara also recalled stories shared with her by her mother-in-law, Clara, also a Russian Jewish immigrant who arrived in America when she was about 18.

Said Barbara: “She traveled here alone. She was part of a large family and her older brother, who had arrived sometime before she did, was bringing members of his family to America one at a time as he earned money to do so.

“The family came from Kiev. They were a Jewish family and in Russia, they had a horrible life.”

Russian Jewish people left often to escape persecution or poverty. Within her mother-in-law’s family, there were eight children. They were brought to America and then to Chicago.”

Barbara said she believed Louis and Clara met in Chicago, but she couldn’t be sure. They were married in 1925.

Times were different then, she said. “People often didn’t speak English. Clara and Louis’ families spoke Russian and Hebrew or Yiddish.”

By the time Louis and Clara were married, Barbara said, Louis was established enough to have a house. The couple gave birth to Milton, their only child, in 1927. He was born in Fort Atkinson.

Building a business

Louis and Clara began operating their scrapyard business from a barn behind their home.

Barbara recalled: “Clara stayed home, but she helped with the business. Scrap was brought to the barn at the house where Clara would operate the scale and weigh it.”

Scrap could be brought to the property by area residents or picked up by Louis, she said, adding that operating a scrap business from home in a family barn was not unusual back then. She recalled her grandfather doing the same thing from a barn on his property in Chicago.

The home owned by Clara and Louis was in the middle of town, across the street from where the Methodist Church is today on Whitewater Avenue. There is an office building there today, Barbara said.

Clara’s role as a scale operator was no small contribution, Barbara said.

“When you buy scrap, you have to weigh it; that’s how you get paid,” she said adding: “Clara was very good with numbers. She was uneducated by today’s standards, but she was smart.”

As Clara raised Milton and helped out with the business, Louis collected scrap and looked for ways to grow the business by finding new markets, Barbara continued.

Louis also worked to find foundries for the different types of materials. Eventually, new markets were developed and the couple began recycling metals, rags and paper.

The arrival of World War II

The business really began to grow with World War II, Barbara said.

“With the war, the scrap industry became a high priority war industry. Metal was needed to make tanks, and guns, and trucks. The war needed scrap, and Louis wanted to grow, but he was limited in what he could do on his little urban lot. He started looking for new land,” Barbara said.

The land known locally as the former Loeb-Lorman scrapyard was back then a wetland, Barbara said, adding: “Nobody wanted it.”

In the 1940s, Barbara noted, “there was a lot of prejudice against Jews and scrapyards. When Louis looked for land, the only place the city wanted him to consider was the swamp, and they wanted him to go there with the understanding that he would fill the land in.

“People like clean industries. They didn’t want a scrapyard in their backyard,” Barbara said, adding that the then-city council and Louis struck a deal: Louis would fill in the land and make it useful and the council would work with him to meet the requirements for his permits.

Barbara described the days leading to the purchase of the land on the city’s north side as “difficult” for Louis. At the time, some residents were circulating petitions against the scrapyard’s expansion, she said.

“Immigrants have fortitude,” Barbara said, and Louis also had people in the community who liked him and were helpful.

“People in town encouraged Louis to work it out and he ended up buying the marsh with the understanding that he would fill it in to expand the business. He was doing well financially because of the war, and filling it in was not hard. There are always people who have fill like broken cement, dirt, gravel,” Barbara said.

She believed Louis purchased the land known today as the Loeb-Lorman site in 1940 or 1941, she added. The land is documented in three parcels, identified as 115 Lorman, 600 Oak and 205 Hake streets.

An advertisement for the Lorman Iron and Metal Co., found in the Hoard Historical Museum archives notes that the “modern processing facility at 115 Lorman Street was built in 1947.”

Barbara and Milton

Barbara and Milton met at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She was pursuing an undergraduate degree in English and he was attending law school.

Barbara was 20 years old and Milton was about 25 when a decision was made to move to Fort Atkinson where the newly married couple planned a temporary stay while Milton was, as a former ROTC student, preparing to receive military orders.

“The Korean War was winding down and then the war ended and Milton didn’t go,” Barbara said.

After they arrived in Fort Atkinson, Milton completed his law degree and went to work at the scrapyard with his dad.

Said Barbara: “While he worked at the yard, he practiced law a little bit. One of his friends suggested he might like being an assistant DA (district attorney), but his source of income was at the scrapyard.

“Thorpe Merriman was the district attorney at the time for Jefferson County. Milton went to work at the courthouse as his assistant, working part-time in the DA’s office.”

With family in Madison and serving as a stay-at-home wife, Barbara described her early life in Fort Atkinson as a “bit lonely.”

In 1954, a year after arriving, Barbara gave birth to Carol, the couple’s first child. In the years that followed, the family grew by two more children: William, born in 1959, and David, born in 1963.

Over the years, Barbara said, she found a nice life in Fort Atkinson and the family business grew.

Barbara described her own experience with the yard as mostly “hands-off.” She would visit, and if office workers were very busy, she might answer the phone, she said.

Upon her arrival into town, Barbara said, the scrapyard was already operating from the north side of town. The building standing in the entranceway today had already been built and was used as office space and it had a scale. There also was a drive-on scale in front of the building.

Metals coming into the yard were categorized as ferrous, meaning with iron, or non-ferrous, which, Barbara said, “is everything else you can think of without iron.”

The most valuable scrap was stored inside where it was cleaned and cut into smaller sizes.

“It was very hard, dirty work,” she said.

As the company enjoyed success, it expanded into the aluminum business, and began recycling glass and plastics.

During the yard’s best years, it had about 40 employees, she added.

“I was a supportive wife, but the scrapyard was a man’s world,” Barbara said.

At home, Milton would arrive each day for lunch and the couple would talk about plans for the business and the challenges it faced.

“This is the commodities industry. Things changed with the economy; it is very tied to the auto industry, which is very dependent on scrap iron. When there is a recession, it hits the scrap industry pretty hard,” Barbara said.

In the early 1970s, the American economy fell into a recession which, online documentation states, caused economic stagnation between 1973 and 1975.

Milton worked at the yard until the time of his death in 1979. He had a heart attack and died at the age of 53. At the time, he was a member of the Wisconsin Legislature, serving as a state representative in the 39th Assembly District. He was serving the first year of his second term.

When Milton died, Barbara said, she became the sole owner of the scrapyard. Earlier, when Louis died in the mid-1970s at the age of 78, he left the business to the couple, she said. Clara survived Louis, also dying in the 1970s.

Barbara continued to own the yard until she sold it to the Loeb family in 1984, she said.

In the years that followed Milton’s death, Barbara found her own life in politics.

A seat held by Sen. Peter Bear became available after the senator resigned. A special election was held and Barbara, at the urging of some of Milton’s supporters, decided to make a run, she said.

Barbara won the seat in 1980, and continued to serve in the state senate, winning three consecutive four-year terms, ending her career in 1994, when she was defeated in a primary by Scott Fitzgerald.

Today, Barbara said, she will soon be 89. She describes herself as retired, adding: “I’ve been active in community service on a number of boards and commissions doing unpaid public service, which I’ve enjoyed immensely.”

Living in Fort Atkinson has provided her with opportunities that she might not have found in a larger city, she said, and the community has brought her many interesting friendships and it gave her children freedoms which children growing up in larger cities may not have had, she said.

Thinking ahead about the now city-owned former Loeb-Lorman property, she said, she hoped it would find a future commercial use.

“It really is a commercial area,” she said.

A related story about future plans for the Loeb-Lorman site is found here: https://fortatkinsononline.com/city-to-begin-second-phase-remediation-process-at-former-loeb-lorman-site/.

Among materials archived at the Hoard Historical Museum is this photograph of Louis Lorman, taken in 1914.

Two above photos: the Louis and Clara Lorman home serves as the family’s first scrapyard. The home and barn were once located on what is today Whitewater Avenue. The couple was married in the mid-1920s and began living in the home. Courtesy of the Hoard Historical Museum.

Employees load scrap. Photo courtesy of the Hoard Historical Museum.

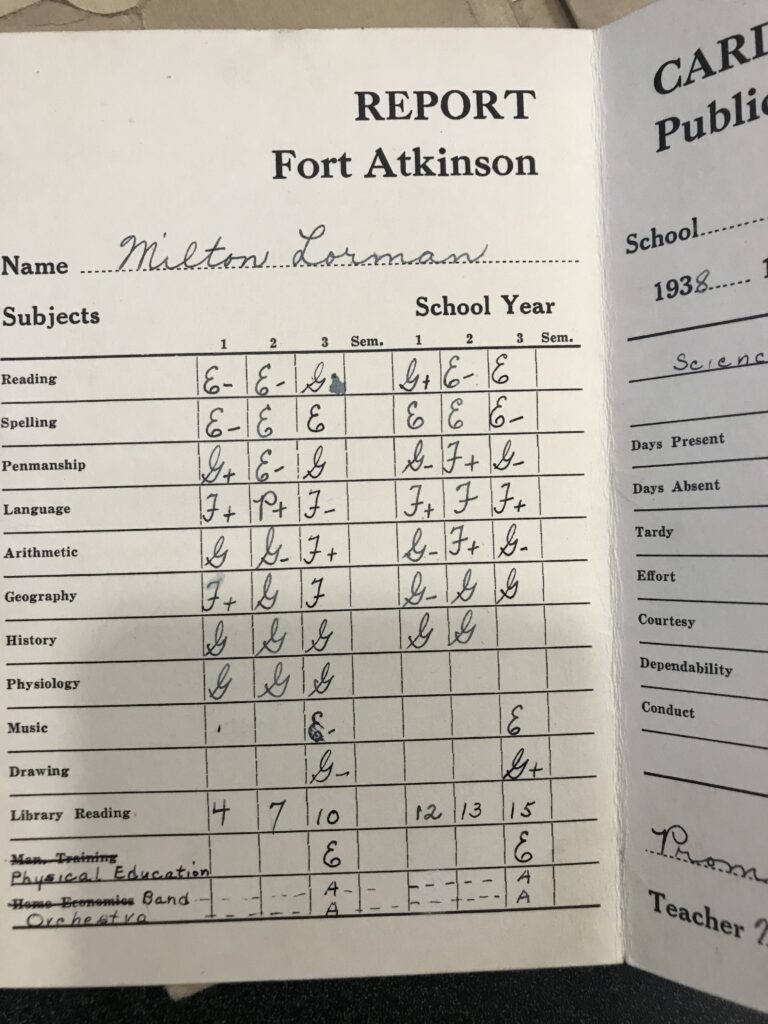

Two above photos: Milton Lorman’s Fort Atkinson elementary school report card from 1938. Courtesy of the Milton Historical Museum.

Pictured at right, Milton Lorman in uniform. According to information found on the Wisconsin Historical Society website, Lorman graduated from Fort Atkinson High School, next earning a business degree from UW-Madison in 1950. He earned his bachelor’s of Law (LL.B) degree in 1953 and his law degree in 1966. Lorman served in the U.S. Navy from 1945 to 1946 and the Army Reserve from 1953 to 1969. He served during his life as president of the Lorman Iron and Metal Company, and in public life as an assistant district attorney in Jefferson County and a municipal judge. He was elected to the Wisconsin State Assembly in 1976 and again in 1978. He died, having suffered a heart attack, while serving his second term. Photo courtesy of the Hoard Historical Museum.

The Lorman Iron and Metal Co. processing facility at 115 Lorman St. The facility was built in 1947. Courtesy of the Hoard Historical Museum.

Trucks transport materials to and from the Lorman Iron and Metal Company’s scrapyard. Courtesy of the Hoard Historical Museum.

Two photos above: Advertisements for the Lorman Iron and Metal Co. Materials supplied by the Hoard Historical Museum.

An arial photograph of the Lorman scrapyard taken in an unknown year. Courtesy of the Hoard Historical Museum.

Barbara Lorman poses for a photograph with Tommy Thompson. Lorman served as a Wisconsin State Senator between 1980 and 1994, when she was defeated in a primary by Scott Fitzgerald. During those years, Thompson served as minority leader of the Wisconsin Assembly between, 1981 and 1987, and as the 42nd governor of Wisconsin between 1987 and 2001. Thompson serves today as the interim president of the University of Wisconsin System. Photo courtesy of the Hoard Historical Museum.

This post has already been read 6390 times!

What a delightful article about a delightful lady. Thank you!

Thank you for the excellent historical account of my Grandparents, Father and Mother’s work. Growing up in a small town, working and playing at the scrap yard and roaming the area with childhood friends all good memories.

My pleasure, David. Thank you for the kind words. Fascinating history and success story. Eager to see what comes next for that piece of land.

I love your articles and wonder how I can get on your list to follow you by email. Sometimes I find them in Kent’s class letters.

You may remember me from the Black Hawk Hotel. I now live in AZ for the past 21 years.

Joyce Sprengel

Hi Joyce, thanks for reading and inquiring about our “follow us” button. At the bottom of any story on our site, you will find a series of three buttons. Two are blue, and labeled “Share on Facebook,” and “Tweet,” respectively. The third is green, and shows the email icon. It has the words “Follow us” on it. Click that button, and the next screen to appear will prompt you for an email address. You can sign up to receive a daily brief of all the stories we posted each day sent to your email. You can also follow us on Facebook if you use it. Just go to Facebook, search Fort Atkinson Online, and when our page comes up, click “follow.” Hope that helps, and again, thanks for reading!