Editor’s note: This is the second in an ongoing series titled: “Evergreen stories,” which features the history associated with Fort Atkinson’s Evergreen Cemetery and the people who are interred within. President of the Evergreen Cemetery Association Brad Wilcox has described the cemetery as “an outdoor museum,” and serves as a source for finding and sharing the stories featured within this series.

By Kim McDarison

Fort Atkinson resident and Hmong-American Solo Yang said he and his siblings knew little about their father’s service during the Vietnam War. When Wang Chou Yang died in June, his children began researching the war’s history and the situation in which many Hmong families, like their own, found themselves after the United States withdrew from the war in 1973.

Solo was 4 when his family fled Laos, he said. He is one of nine children, four of whom were born in Laos, and five of whom were born in the United States. He believed his oldest sister, Choua, then 8, likely remembered first-hand more about the family’s departure from Laos. She also was the person responsible for much of the history shared by the family within Wang Chou’s obituary, which recounted some of his time during the Vietnam War, as he served within an army comprised of his ethnic countrymen in support of the U.S. Military.

The history was not often talked about within his family, Solo said, but upon the occasion of his father’s death, it became important because his father, although reticent about the war throughout his life, remained proud of his service, and wished to be buried with military honors.

Looking back at the history and the stories his father never shared, Solo said: “It would have been nice if he would have told me, but I understand why he didn’t. I’m sure doing work like that, he had to take lives, and it would have brought bad memories.”

About a year before his father died at the age of 76, he became ill, Solo said. He was diagnosed with Creutzfeld-Jakob Disease, which Solo described as a human equivalent to Chronic Wasting Disease found in deer.

“The neurologist told us it was just bad luck; one in one million chance of getting it. We don’t know how he contracted the disease,” he said.

When his father was dying, he told the family that he wanted a military funeral, Solo said.

“He said he wanted to wear his dress blues from the U.S. Army. The uniform was from his time when he served in a Hmong group called the National Defense Force. They were a group that helped out with FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency),” Solo said.

He was part to that group while living in the United States, Solo added.

“He had a uniform from his association with that group. He was attached to his history and was proud to have served with the U.S. military back then (in Laos) and he was proud to be attached with the group that worked with FEMA,” he noted.

Still, Solo said, when Wang Chou, along with his family, escaped from Laos, he, like so many Hmong refugees, burned and buried his military uniform, weapons and any pictures taken during that time. To have such things in his possession would have put everyone in danger.

According to Solo and his brother-in-law, Lee Her, who is married to Choua, many of the Hmong who arrived in the United States, and other countries, share the same story: They fled in fear for their lives in the wake of what the two men described as a genocide that was taking place in Laos.

Both expressed a need for the story of the Hmong to be told, noting that families living in America today helped the United States during the Vietnam War, and when the Americans left the country, the communists in charge, allegedly, history recounts, waged war on the Hmong.

Both men pointed to a book by Jane Hamiton-Merritt, titled: “Tragic Mountains: the Hmong, the Americans, and the secret wars for Laos, 1942-1992.”

The book documents what it describes as a “secret war,” during which the American military engaged with the Hmong, helping them to form a gorilla army under the leadership of General Vang Pao. The group came to be known as the Secret Army or the Hmong Army. It fought against the Pathet Lao, also known as the Lao People’s Liberation Army, and the People’s Army of Vietnam. Both had connections to the Communist Party of Vietnam.

In 1975, Vang Pao was among those emigrating to the United States after the communists took control of Laos.

Escape from Laos

While Solo remembers little of the journey, he does know the story.

“We escaped across the MeKong River. We were on a boat. My father paid somebody to get us across with a boat,” he said, noting that the river runs between Laos and Thailand. Large numbers of refugees were gathering in refugee camps in Thailand, he said.

The family fled after hearing “through the grapevine” that the Vietnamese were coming for anyone who helped the Americans during the Vietnam War, Solo said.

His father was among those who joined with a gorilla group that worked to help the Americans. He was 16 when he joined, Solo added.

According to information presented by the family in Wang Chou’s obituary, he was recruited by the United States in 1961 and sent to Thailand for military training to serve alongside the United States Army. He and others “served, suffered or sacrificed in the secret war in the years 1961-1975 in support of the armed forces of the United States.”

The obituary notes that some 35,000 Hmong soldiers lost their lives protecting trapped, lost or captured American soldiers and pilots in Laos.

During that time, the obituary continued, Wang Chou performed pararescue services. He was dropped by parachute behind enemy lines, tasked with the job of locating and rescuing downed pilots and injured soldiers. Additionally, he served as a paramedic and military chaplain, providing first aid and administering last rites.

During his service, he achieved the rank of two-star lieutenant, according to his obituary.

In 1963, Wang Chou married Nao Thao. With the withdrawal of the U.S. military from the Vietnam War, the couple and their children — Choua, Chia, Solo and Kennedy — fled their homeland as refugees.

After the Americans left, the Hmong had to leave Laos or be killed. They traveled from the north of the country to the south where they could cross the river into Thailand, Solo said.

Lee’s family also fled the country after the Americans left.

As an ethnic group, the Hmong were easy to identify and they were targeted, Lee said.

Those looking to escape the country traveled by car or walked, often at night. At the time, Lee said, he was 12. He recalled that his in-law family drove across the country from the north to the south at night.

Said Lee: “There was an underground that would hide people and help them get to the river. The underground charged a high fee; they made money running refugees from Laos to Thailand. If you ran into a patrol, they shoot you down, or you could drown from capsizing of the boat. Many did die.

“My in-law family, they made it. Then they were staying in Thailand for a short while. There were refugee camps in Thailand where people would resettle and be processed. It was a compound. There were multiple camps, and at least two major ones. At the camp, you could be processed and sent to almost anywhere. Some families were sent to Australia, France or Canada, but mostly they were sent to the United States.”

Describing the camp, Lee said “There were a few thousand, children, families, everyone.”

Lee said those traveling from the camps to other countries did so under sponsorship and in consideration of their status with the military.

“The people at the camp decided who was in the largest danger and needed to leave more quickly. They would match the refugees with a sponsor. Because of Solo’s father’s relationship with the military, the family was in the camp for less than a year,” he said.

Lee recalled that both his and his in-law family left Laos in 1975.

“We were just kids then,” Lee said of himself and his wife, noting that they were later reunited in America and married.

“This is not just our family’s story. It is the story of the Hmong people,” Lee said.

A life in Fort Atkinson

In 1976, Solo and Lee recalled, the family of Wang Chou arrived in Fort Atkinson.

They were aided through sponsorship by the Trinity Lutheran Church of Fort Atkinson.

After the family arrived, it grew to include five additional children: Malia, Nathalie, Amy, Elizabeth and Abraham, Solo said.

Upon its arrival, the family lived in a dwelling that was provided by the church.

Wang Chou found a job working at NASCO, and later Thomas Industries, in Fort Atkinson, and then at Schweiger Industries in Jefferson.

According to Solo, the family lived in several locations in Fort Atkinson, including a rented home next to PJ’s Bar and a duplex on the south side of town near Luther Elementary School.

His parents purchased their first home on West Cramer Street.

All the while, he said, his parents dreamed of owning a hobby farm where they could grow their own produce. The dream came true in the late 1990s when they purchased a nine-acre farm and began raising meat birds, including pheasant, chickens and doves, and vegetables which they sold at the Fort Atkinson and Whitewater farmers markets.

Wang Chou retired in 2010, his obituary reports. At the time, he was working for Friskies Purina in Jefferson.

Making a military funeral

After Wang Chou died, the family began making plans to provide him with a military funeral.

Help from the U.S. military did not come as readily as they had hoped: “Dad was not given full military honors by the U.S. government because he wasn’t directly recruited by it,” Solo said, adding that he was never officially a member.

The government representative with whom they were working expressed disappointment that the family’s request could not be granted, citing protocols, Solo said.

Not knowing how best to proceed, the family sought help from Nathan Dunlap, the owner and director of Dunlap Memorial Home in Fort Atkinson.

Nathan and the family pooled ideas and resources to create a funeral they believed would honor Wang Chou, Solo said.

The result included a horse-drawn caisson contracted through Hoof Beats Express LLC in Oconomowoc.

“Dad wished for that because back in Laos, when a high-ranking officer passed away, they had a horse-drawn carriage,” Solo said.

In addition, Dunlap placed the family in contact with American Legion Post 166 Sergeant-at-Arms Richard Miles, who helped organize and assemble an honor guard, and the necessary individuals to perform Taps and a 21-gun salute.

With honors, Wang Chou was placed in his final resting place in Evergreen Cemetery on July 9, cemetery association president Brad Wilcox said.

A monument was placed over the grave on October 31.

An inscription reads: “Wang Chou Yang serve alongside the United States Army in the Secret War in Laos during the Vietnam War from 1961-1975. He achieved the rank of Two Star Lieutenant. His sacrifice was not about bravery but the fight for freedom for his people. Freedoms we should never take for granted.”

The plight of a people

Sharing some history about the Hmong people, Solo said his ancestors were originally from China.

“The true Hmong had blonde hair and blue eyes. In China, the Chinese wanted to dominate our genes,” he said, which, over time, changed the appearance of the Hmong people.

Historical accounts note that conflicts between the Hmong and other ethnic groups in China led to migrations of the Hmong people, for whom a time of unrest and displacement began in the late 17th century, lasting throughout the 19th century. During the Qing dynasty — from 1636 to 1912 — repressive economic and cultural reforms led to conflicts and large-scale migrations during which time many Hmong immigrated to Southeast Asia. During the same period, the Hmong were subjected to persecution and genocide.

During the 19th century, the Hmong migrated to Northern Vietnam where they worked to establish their community in the mountains.

While struggles for control between overlords existed in the region, the Hmong harmonized with the ethnic groups. After World War II, some of the Hmong developed relationships with the French military, but after the Viet Minh victory, in 1941, the Indochinese Communist Party became dominate in the region and the pro-French Hmong fell back to Laos and South Vietnam.

In Laos, some Hmong participated in fighting against the Pathet Lao Communists, while others enrolled in the People’s Liberation Army. Some tried to avoid conflict all together.

The Vietnam War began in 1955, with America entered the war in a limited capacity. America’s involvement escalated over a 20-year period, which peaked in 1969, with 543,000 troops stationed in the country.

Solo said he believed his father joined the conflict and fought alongside the Americans in the name of freedom for his people.

Lee said he believed that without support from the Hmong soldiers, the American military would not have survived in the northern part of Vietnam as long as it did.

Arriving in the United States, he said, “we feel like we made it home because we always knew who we fought on behalf of.

“Here in America, people are not always nice to the Hmong. Our families risked our own lives and we are not being recognized.”

He hoped, he said, as more people develop an understanding of the history of the Hmong and the military landscape during the Vietnam War, they also will develop a deeper appreciation for the people who supported America and continued, as Wang Chou did, to nurture a lifelong devotion to his people and adopted country.

Wang Chou Yang’s obituary is here: https://fortatkinsononline.com/wang-chou-yang/.

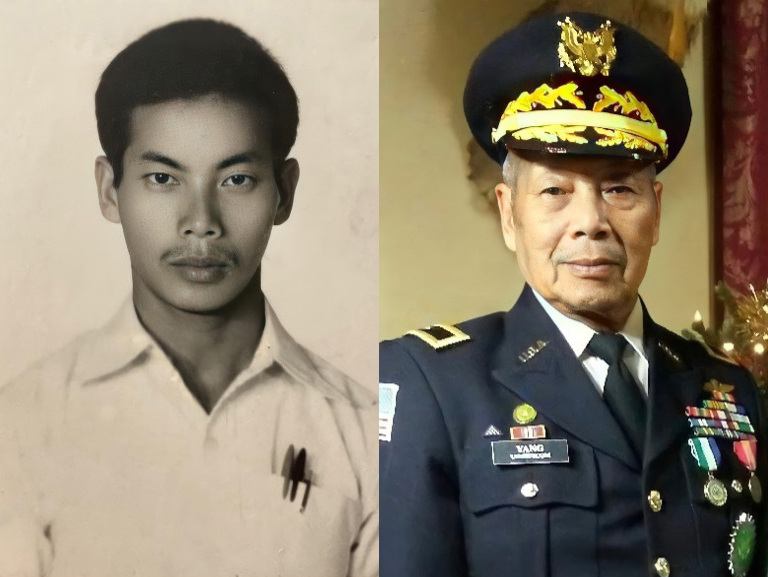

Wang Chou Yang, contributed.

Four photos above: a horse-drawn caisson contracted by the family of Wang Chou Yang brings the late soldier through Evergreen Cemetery and to his final resting place.

An honor guard, arranged and conducted by Fort Atkinson area veterans groups, pays tribute to Wang Chou Yang’s military service during his funeral held in June.

A monument, describing his service during the Vietnam War, identifies the final resting place in Evergreen Cemetery of Wang Chou Yang.

Photos, unless marked “contributed,” are courtesy of Brad Wilcox.

This post has already been read 2518 times!

This is a great story of a war hero and his family moving to America to have a better life. Thank you for publishing this story.

What a beautiful and touching story. Thank you for sharing. May we ever be mindful of the dedication to and the sacrifices made for freedom. Thank you to all who worked together to make this honor possible. Knowing the people of Fort Atkinson, I would have expected nothing less.