Editor’s note: The following story has been shared for publication by The Badger Project, which, according to its website, is a nonpartisan, citizen-supported journalism nonprofit in Wisconsin. A link to the publication is here: https://thebadgerproject.org.

By Peter Cameron/The Badger Project

The number of law enforcement officers in the state ticked down again in 2022, setting a new record for the lowest statewide total since the Wisconsin Department of Justice started tracking the numbers in 2008.

To relieve some of the burden on law enforcement agencies, and attempt to de-escalate encounters between police and civilians, some cities and counties across the state are experimenting with sending non-police employees to answer some 911 calls.

Wisconsin has fewer than 13,400 law enforcement officers at the moment, according to the state’s Department of Justice. That’s down from 2021, when the state counted more than 13,500. The record high is nearly 14,400 in 2008. These totals exclude officers who work exclusively in correctional facilities.

Although the decreases are small, they are occurring while the state’s population is on the rise. In the last decade, Wisconsin grew to nearly 5.9 million residents from about 5.7 million, according to the U.S. Census — an increase of about 4%.

Exacerbating the law enforcement shortage is Wisconsin’s unemployment rate, which sits at a near-record low of 2.9 percent, below even the national rate of 3.5 percent, which itself matches the lowest level in 50 years.

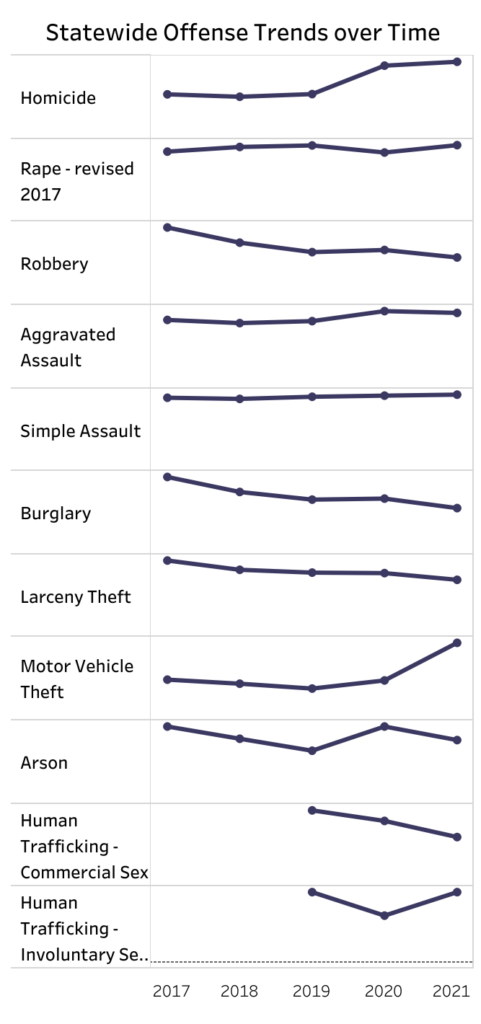

And while some crime, including burglary and theft, is down statewide, the tumultuous pandemic years have brought a rise in violent crime such as homicide and assault, according to data from the state DOJ. Wisconsin mirrors a rise in most violent crimes across the country.

Milwaukee has taken the brunt. In 2020, the city set a record for its highest number of homicides in one year: 190. Last year, it broke that new record by reaching 197. And with 160 homicides recorded by the end of August, the city is on pace to break that record again this year.

The “cop crunch” has been a concern for years, as demographics and priorities of younger generations shift. But it has become more acute recently as industries across the board struggle to find workers in the post-pandemic economy.

Jim Palmer, executive director of the Wisconsin Professional Police Association, the largest law enforcement union in the state, said he believes that a number of factors have contributed to the crunch.

“Budgetary constraints that impede an agency’s ability to maintain staffing levels, the well-publicized, broad-brush criticisms that surround the profession in the wake of law enforcement controversies, regardless of where they occur in the country, and the changing work preferences of a younger generation that can make more money doing a job that is less dangerous, less scrutinized, and less reliant on working conditions such as shift work and forced overtime,” he said in an email.

In a report from the Wisconsin Policy Forum from June of 2020, Wisconsin finished dead last of all 50 states in the percentage of state funding for law enforcement. To balance that, the state’s municipal governments appear to devote a higher proportion of their budgets to police than the national average, the report said.

Many law enforcement agencies do have the budget authorization to hire, but simply cannot land qualified recruits.

The Milwaukee Police Department currently employs about 1,600 of 1,657 budgeted police officer positions, department spokesman Sgt. Efrain Cornejo said. That’s about 3 percent understaffed.

All the way up in Marinette County, Sheriff Jerry Sauve said his office is having “a hell of a time” filling positions.

“We have not been at full staff in our county jail since 2010,” he said.

Sauve sometimes has to make the “painful decision” to pull deputies from patrol to staff the county jail to meet mandatory minimum staffing levels.

“It’s now impacting public safety by lessening the patrol personnel out there,” he said.

Attempts to hire and retain more officers

Law enforcement openings used to attract many applicants. Not anymore.

“When I broke into this business in 1983, there were well over 100 applicants” for openings, Sauve said. Now, “we’re getting 6, 8” applicants.

Sheriff’s offices and police departments need to start promoting themselves and recruiting year-round, Palmer said.

He pointed to the Wausau Police Department, which he said has “maintained a consistent and relatively inspirational social media campaign to highlight the efforts, diversity, and service of not only the department, but the officers that work within it. This may help explain why that agency reports not having the same recruiting challenges that we see elsewhere.”

Wausau Police Chief Ben Bliven said in an email that his department was about to swear in four new officers to reach full staffing levels.

“But I would say we are still struggling with getting applications,” he added. “Recruiting does continue to be a challenge for us compared to years in the past.”

Palmer also said local governments must invest more in law enforcement to hire more officers at higher pay, as well as investing in a range of services, including community-oriented policing.

Marinette County has enacted a premium pay system to help retain employees, Sauve said. For every hour a law enforcement officer works, the county contributes an extra dollar or two toward a bonus check. Sauve said he also is pushing county government to move his correctional officers into a different employment category that grows pensions faster.

Other ideas: Non-police responses to 911 calls

Some cities and law enforcement agencies in the state are using civilian employees to ease the burden on police.

The city of Madison, home to what experts call one of the more progressive police departments in the state and country, launched an initiative in September 2021 that dispatches an EMT and a crisis counselor to some 911 calls that don’t require a police presence.

As of August 2022, the Community Alternative Response Emergency Services (CARES) program has answered more than 800 calls that police normally would have, said Madison Fire Department Assistant Chief Che Stedman, who oversees the program.

In July, the city announced it was adding a second CARES team, allowing it to operate from two sections of the city from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. City officials say they eventually hope to make the program available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Milwaukee is slowly moving forward on plans for a similar program, but is looking for more than $900,000 to fund it. The Law Enforcement Action Partnership (LEAP), a nonprofit consisting of police, prosecutors, judges and others in law enforcement, would run the program.

The Milwaukee Police Department already employs about ten community service officers, a program in place since 2015, Cornejo said. These are civilians who respond to non-emergency and low-priority calls, including theft, vandalism and traffic incidents without injuries.

In the north-central part of the state, the Wausau Police Department and Marathon County Sheriff’s Department have partnered with local healthcare organizations to create the Crisis Assessment Response Team (CART), which pairs plain-clothes law enforcement officers with a crisis counselor to handle some mental health calls. By reducing the number of mental health detentions, which must be performed by a law enforcement officer, the team has saved taxpayers about $3 million per year, officials from the program estimate.

The concept came from the city of Madison, which has embedded crisis counselors in its police department for years.

Easing law enforcement workloads could allow officers to direct more resources to preventing and solving violent crime, experts say.

Instead of “Defund the police,” some law enforcement reformers have promoted a different slogan: “Solve every murder.”

Graphic supplied by The Badger Project/Courtesy of the Wisconsin Uniform Crime Reporting Data Center.

The total number of law enforcement officers in Wisconsin has dropped to its lowest level since the state Department of Justice started tracking it. Graphic by The Badger Project.

Police close public access to a street near the scene of a crime. File photo/Kim McDarison.

This post has already been read 1075 times!