By Kim McDarison

Members of the Whitewater Unified School District Board of Education Monday approved the hiring of a new English language learning program coordinator and a part-time instructor.

During Monday’s meeting, school district Superintendent Caroline Pate-Hefty presented a proposal to offer multilingual learning services to students who are native English speakers and those learning English as a second language.

“If we do this well, it could mean that we are graduating students to be multicultural, bilingual and bi-literate,” Pate-Hefty said.

After the presentation, the board approved the hiring of a coordinator for the new program, contingent upon the presentation of a job description, which is anticipated to be brought before the board during its next meeting.

The board also stipulated that the person filling the coordinator’s position must be qualified to teach English language learners in a classroom.

Additionally, the board learned that Lakeview Elementary School was served by one part-time paraprofessional who works with students learning English. With a recent addition of students at Lakeview, bringing the school into compliance with state statutes would require at least one full-time instructor for the building’s English language learning population, Pate-Hefty explained

The board approved the necessary hours to bring the school into compliance.

Enrollment and need

Aided by slides, Pate-Hefty shared a proposal to increase programming opportunities for students coming into the district in need of English speaking skills while helping them maintain their native language. The result, Pate-Hefty said, would be more multilingual students. Further, she said, the program could also be offered to native English speakers who, by opting into the program, could become multilingual by learning to speak a second language.

Pate-Hefty said her proposal was modeled after a program which enjoyed success in the district where she previously served.

Pointing to a slide presentation, titled: “Multilingual/English Language Learner Program Response to Student Needs,” Pate-Hefty said benefits multilingual learning students enrolled in the program could enjoy included: moving away from the concept that students should only learn English; subtracting the concept of taking away their ability to speak Spanish, and recognizing the benefits associated with speaking two languages.

The program would also allow all students to participate in multilingual opportunities and offer support to students learning languages earlier in their K-12 educational careers.

Pate-Hefty next shared a slide showing different brain scans. Information on the slide indicated that “brain imaging techniques, such as fMRIs, have shown that multilingual brains tend to activate the linguistic portion of their brains even when not engaged in linguistic tasks. This leads researchers to believe that the brain’s ability to connect skills tends to enhance cognitive function over time.”

The slide further indicated that “bilingual brains tend to show higher levels of activation to auditory stimuli overall.”

Among other statistics shared, according to Pate-Hefty, between 2010 and 2018, the number of U.S. job advertisements including the ability to speak Spanish as a desired skill increased by about 150%.

Citing U.S. Census Bureau statistics, she said, as of 2018, the number of residents in Wisconsin who speak a language other than English was reported at 483,952.

Also, she said, the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages research cites five major research-based studies that show students who learn foreign languages perform better on standardized tests.

Within her presentation, Pate-Hefty defined several terms, including that of “newcomer,” which, she said, describes “foreign-born students who have recently arrived in the United States.”

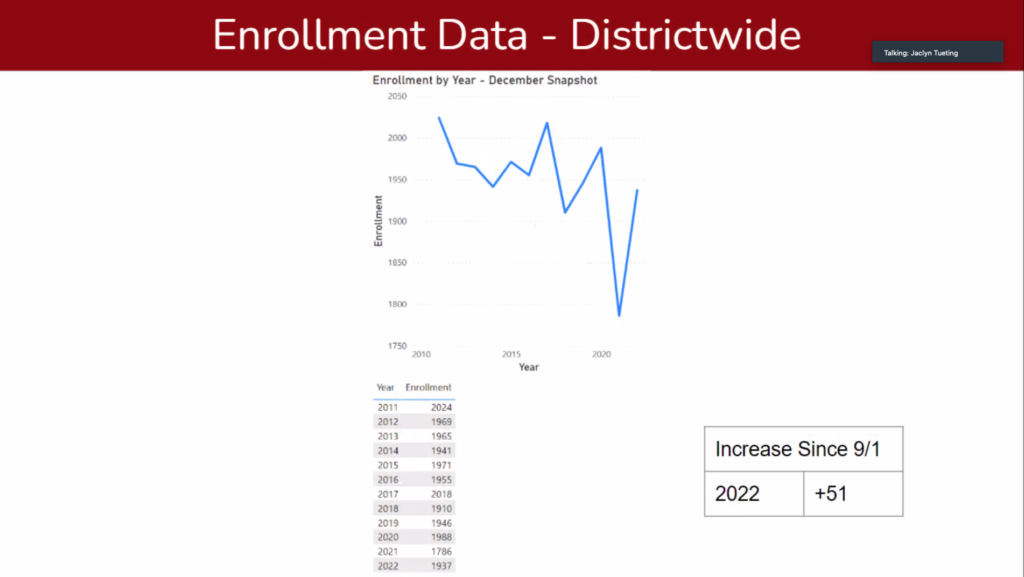

Looking at districtwide data, Pate-Hefty noted that since Sept. 1, enrollment has increased by 51 students.

Pointing to a “December Snapshot,” she said, after sustaining a dip in enrollment in 2021, the district’s enrollment has rebounded to similar numbers as those recorded before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. A slide showed enrollment in 2019 at 1,946, and in 2020, at 1,988. In 2021, enrollment numbers decreased to 1,786. In 2022, Pate-Hefty said, referencing the latest data receive this week, numbers had risen to 1,937.

“We have more than recovered from our COVID loss, and we are only 87 students away from our highest enrollment ever, which was in 2011,” Pate-Hefty said.

Looking specifically at Lakeview Elementary School, Pate-Hefty said, as of Sept. 1, the school saw an increase of 15 students. The December Snapshot showed building enrollment at 201 students in 2019; 207 students in 2020; 164 students in 2021, and 179 students in 2022.

“So looking at Lakeview, when I took this data, we were at about 179 students,” Pate-Hefty said, adding that “now” the number is at about 186. “It should be noted that they are 28 students away from their highest enrollment ever,” she said.

Pate-Hefty noted that while it was often assumed within the district that Lakeview has small class sizes, that was not true in all classrooms in all grade levels.

Looking at overall elementary school class sizes, on average, by student, she said, “Lincoln has about 19.2, Washington about 19.1, and Lakeview, 17.5.”

When looking at class size, she said, at Lakeview, it was noteworthy that while it has the smallest average overall class size, it also has the least amount of resources, especially as they relate to students with disabilities and English language learners.

“They have a .5 paraprofessional that can speak Spanish … and our staffing is very different in the other buildings,” she said.

Similar data at Lincoln Elementary School indicated that the building had seen an increase in enrollment of one student since last September. Data was as follows: in 2019, the school had 376 students; in 2020, the school had 388 students; in 2021, the school had 353 students, and in 2022, the school has 375 students.

“They are 13 students from our highest enrollment just before 2020. Lincoln’s zone is our largest according to the last board-approved map that you can find. It does house a majority of move-in students,” Pate-Hefty said, adding that with regard to multilingual students, the building would require a “tremendous amount of support” to “continue doing what’s right for all kids.”

At Washington Elementary School, the December Snapshot reported enrollment of 340 students in 2019, 345 students in 2020, 300 in 2021, and 322 this year. The data noted that five new students had enrolled at the school since last September.

Most recent enrollment numbers showed that Washington is 23 students away from its highest enrollment ever, Pate-Hefty said.

Middle school data was reported as follows: from the December Snapshot: 408 students in 2019, 400 students in 2020, 349 students in 2021, and 436 students in 2022. Nine students have enrolled at the middle school since last September.

Looking at the high school, Pate-Hefty noted that in 2019, the school had an enrollment, according to the December Snapshot, of 584 students. In 2020, the number was 608. In 2021, 489 students were enrolled at the school, and in 2022, the number stands at 587. Since last September, 17 students have enrolled at the high school.

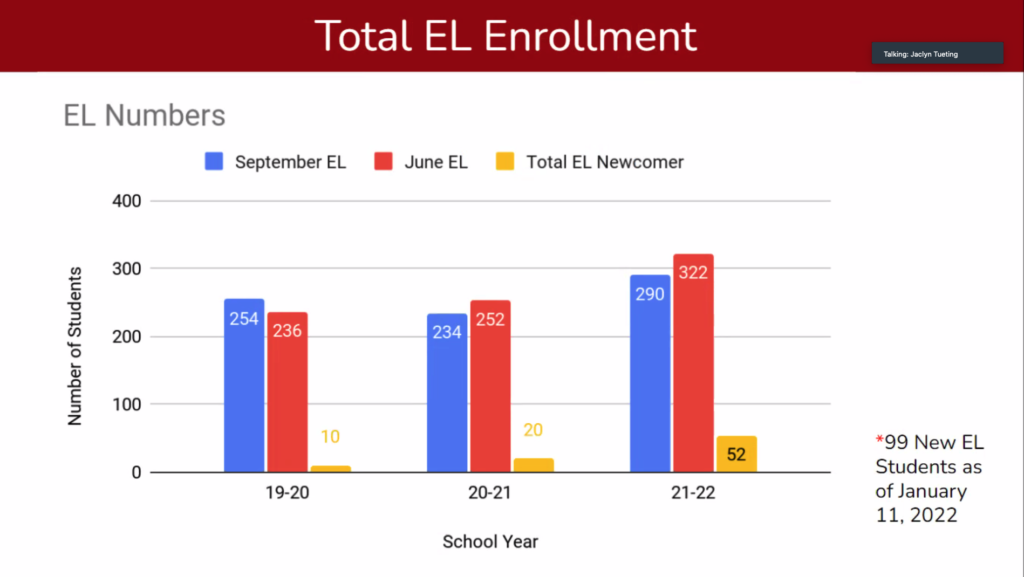

Pate-Hefty next produced a bar graph showing districtwide enrollment of English language (EL) learning students. She noted that 99 new EL students had joined the district as of Jan. 11.

The graph offered total enrollment numbers for EL students counted in both September and June, and a total of EL newcomers for each year. During the 2019-20 school year, a September count showed 254 EL students and a June count showed 236 students. Ten newcomers enrolled into the district that school year.

During the 2020-2021 school year, the September count showed an enrollment of 234 EL learners and a June count of 252 students. Twenty students enrolled as newcomers that year.

This year, 2021-2022, Pate-Hefty reported a September count of 290 EL students and a June count of 322, with 52 students identified as newcomers.

Pate-Hefty noted feedback about the district’s EL programming, offered by the Cooperative Educational Service Agency (CESA) 2, of which the Whitewater Unified School District is a part, which included the following recommendations: that the district create a standard operating procedure including an initial assessment for English language and multilingual learners, along with intake and placement procedures, and consider a model for EL and multilingual instruction, which Pate-Hefty said, would mean all kids becoming multilingual, noting that the district currently uses a “one size fits all” approach for EL instruction.

“So if you are a newcomer, or proficient in English or Spanish, we are treating them all the same way,” Pate-Hefty explained.

Pate-Hefty shared several models showing that multilingual students, who, after entering the district and participating in its current programming, lose their ability to speak their native language, with a drop in that proficiency occurring most dramatically between the elementary and middle school levels.

Staffing

According to Pate-Hefty, to create a program that would equitably address needs across the district for EL and ML learners, additional staffing would be required.

Sharing some district history, Pate-Hefty said: “Years back, Washington was approved for a grant that allows funding for one of several optional strategies. So when you are looking at your numbers, that’s called AGR or Achievement Gap Reduction. This is significant funding that we get over at Washington for this, and it allows us to support staffing needs and we are tremendously grateful for it, but it does only come to one school.”

Pate-Hefty noted that, along with AGR funding, comes research showing effective strategies the district can adopt.

“We can choose from several strategies,” she said, adding that a strategy in use at Washington is limiting class size.

Said Pate-Hefty: “So from K-3 we limit Washington’s enrollment to 18. This limitation … does put some pressure to move those students who start after the year in those grades into the other school buildings. Which is often, first Lincoln, because that’s the closest geographically, and then secondary to Lakeview.

“So when students move in, say, to Washington, and Lincoln becomes starting to get full, then we are moving students with language needs to Lakeview. This has been historically acceptable. Now, however, we have influx that I’m going to show you.

“It really is not equitable when we send students who don’t speak English specifically to Lakeview where … currently, the way it stands, they currently have a .5 paraprofessional. So we are sending potentially students with the greatest need to get the least amount of support.”

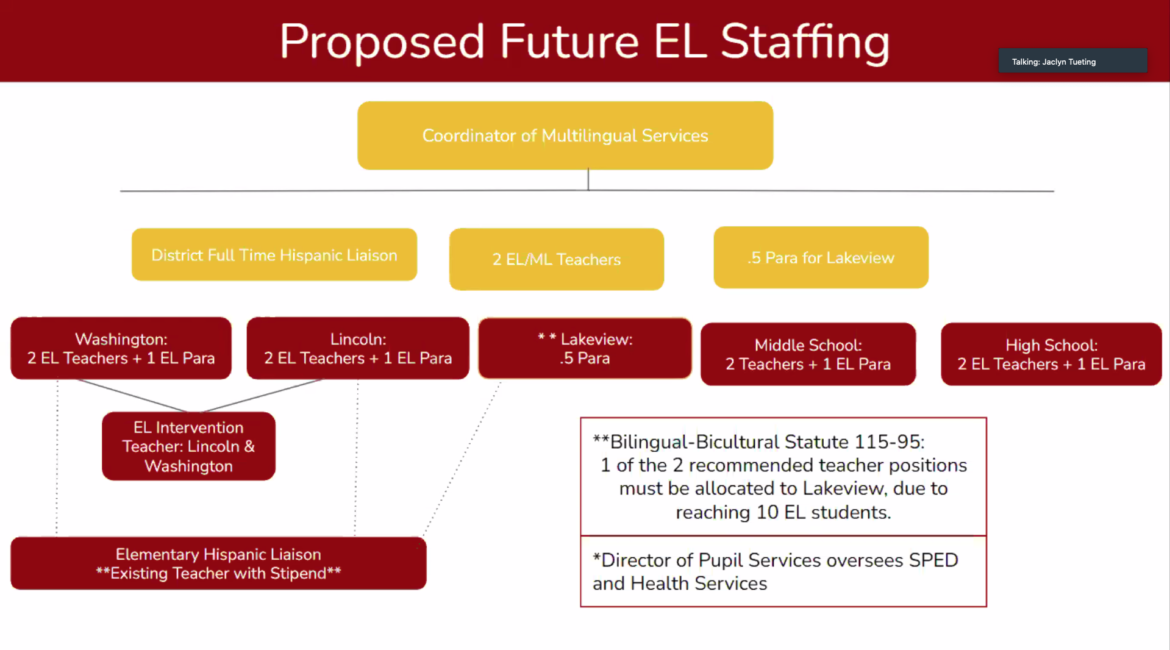

Aided by staffing charts, Pate-Hefty said EL staffing across the district includes two EL teachers and one paraprofessional at each of the district’s school buildings with the exception of Lakeview, which has one part-time paraprofessional.

The district also has an EL intervention teacher who shares time between Lincoln and Washington, and virtually with Lakeview, and a district Spanish liaison, who is funding through a stipend.

The EL intervention teacher is funded by stipend paid through the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) fund, which was extended to schools as part of the CARES act passed in 2020, Pate-Hefty noted, adding that a teacher within the district is filling the role, working nights and on weekends to help meet social, emotional, and medical needs, among others.

English Language staff currently reports to the district’s director of pupil services.

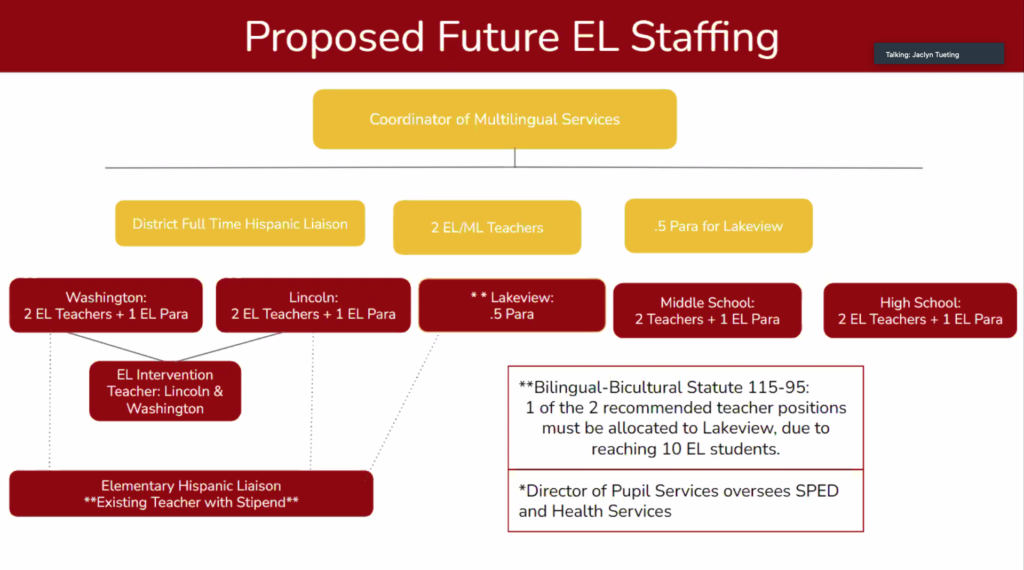

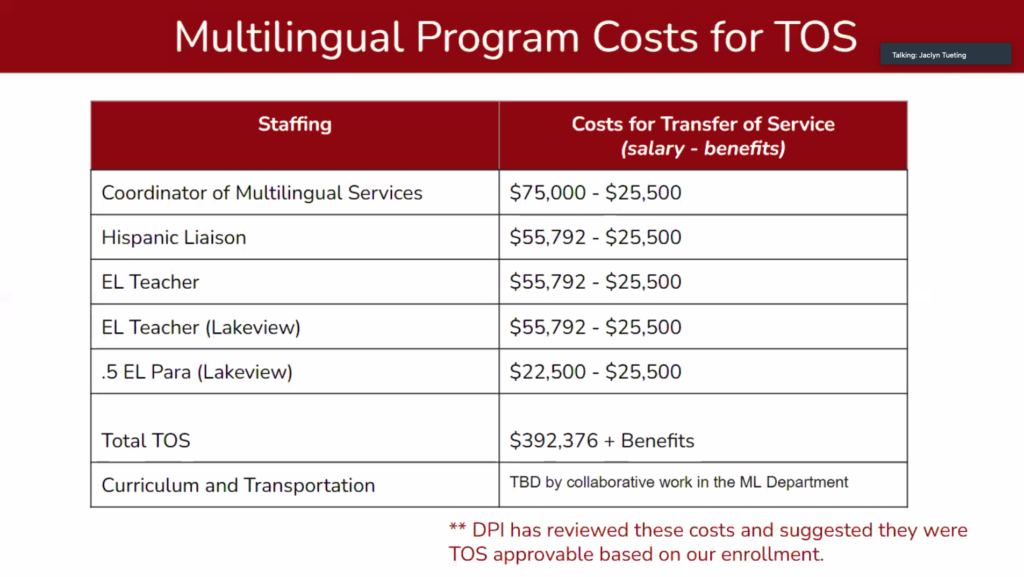

Staffing for a new program, as proposed by Pate-Hefty and demonstrated in an employment flowchart, would include the addition of a coordinator or director of multilingual services, a full-time district hispanic liaison, two additional EL/ML teachers and additional hours added to the paraprofessional position at Lakeview, bringing it to full-time.

Changes depicted on the flowchart indicated that the coordinator would assume EL-related duties currently performed by the director of pupil services. Another priority would include the dedication of one full-time teacher to Lakeview, which, the chart noted, was required by state statute because the school is supporting at least 10 EL students.

Costs, identified as salary and benefits, associated with the proposed staffing changes are as follows: coordinator position: $100,000; hispanic liaison, $81,292; each of two EL teachers, $81,292 (total cost, $162,584), and part-time paraprofessional, $48,000.

Costs associated with curriculum and transportation needed to support the program were listed as “TBD” (to be determined)” by “collaborative work in the ML department.”

Also noted was the potential for funding through the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (DPI) using its enrollment-based Transfer of Services (TOS) mechanism. The district has identified $392,376 in program-related costs as applicable for funding through the TOS mechanism.

Funding

Sharing the presentation with Pate-Hefty, school district business manager Benjamin Prather talked about the TOS mechanism.

“This allows us to request an exemption to exceed the revenue limit based on an estimated cost. The estimated cost is tied directly to new students coming in,” Prather said.

Looking at some district history, he said during “our past revenue limit, we did request a transfer of services for $115,000 for new students that were here prior to the third Friday count.”

Since then, he said, more students have enrolled into the district and he is looking into requesting additional transfers.

Prather said that as he considered the next budget, he would be looking to build a transfer exemption to support the dual language program and to cover costs associated with students in need of additional EL services.

Prather said he had recently reached out to other area school district business managers and learned about the value of using the TOS provision.

Explaining the process, Prather said the revenue limit is tied to enrollment. With more students come more needs, he said, adding, that state statutes stipulate those costs fall on the taxpayers unless the district qualifies for additional aids.

Board member Larry Kachel asked about other possible funding sources including grants and federal aid.

Pate-Hefty said she would encourage program staff to seek grants.

“There is funding for charters in Wisconsin,” she said, adding “we need to be creative with it, but federal is not really provided.”

She reminded board members that the district has 55 students who likely qualify for TOS offsets that the district has not yet claimed.

Referencing a conversation with DPI, Prather said he understood that the 55 students would likely qualify, but there was an “untraditional” component to his understanding of the process.

Typically, he said, districts receive money from a district of origin when a student transfers from one district to another, and a similar process exists when a student transfers in from a district within another state. The students in question are from another country, he said. In his conversations with DPI, he understood they would still qualify because they would “pass Question 1.”

“I pressed DPI pretty hard on this to make sure we would be compliant … as long as these students would qualify as ELL or special ed students, it’s going to tick the boxes,” he said.

Looking at the full program staffing proposal, Kachel said: “So with benefits we are looking at half a million dollars, all funded by local taxpayers.”

Pate-Hefty responded, saying: “About $400,000 is where we estimated, not including curriculum and transportation.

“It would increase the levy,” she added.

A further consideration for the program was space, Pate-Hefty said.

“None of our buildings can currently house a K-5 multilingual program. We don’t have enough room. So it means that we have to make some shifts somewhere. If we want this program to provide access for all students … we don’t have a space for five grades in one place.

“We are just talking about some initial programing and staffing in this proposal that would get us to the place of making other decisions about: Where do we want to go? Where do we want to build this program? What does it look like for all families?” she said.

A graphic shared Monday with Whitewater school board members by Superintendent Caroline Pate-Hefty shows enrollment statistics for the district between 2011 and 2022

A bar graph shared with Whitewater school board members Monday by school Superintendent Caroline Pate-Hefty shows the number of English language learners enrolled in the district over the last three school years.

A flowchart shared with Whitewater school board members Monday by Superintendent Caroline Pate-Hefty shows current staffing within the district’s buildings to support English language learning students.

A flowchart shared with Whitewater school board members Monday by Superintendent Caroline Pate-Hefty shows proposed staffing within the district’s buildings to support a new multilingual learning program. The board approved the hiring of the coordinator’s position, with some contingencies, and added part-time hours to an instructional position at Lakeview Elementary School, bringing it to a full-time position.

The above graphic shows costs associated with staffing a new multilingual program as proposed by Whitewater Unified School District Superintendent Caroline Pate-Hefty.

This post has already been read 1727 times!