By Kim McDarison

Statewide trends in early stage investing — along with money arriving into the state brought by venture capital investors — was a discussion topic recently at the Whitewater University Innovation Center.

Earlier this month some 50 people, many of whom were interested in opportunities for startup ventures as they seek seed money, gathered for a luncheon facilitated by the Wisconsin Technology Council, and its membership arm, the Tech Council Innovation Network (TCIN). The event was sponsored by the Innovation Center in Whitewater and We Energies, according to information released by the Wisconsin Technology Council.

According to the release, the Wisconsin Technology Council is an independent, nonprofit science and technology advisor to the governor and the Legislature. It operates through events, publications and outreach “that contribute to Wisconsin’s tech-based economy.”

Commentary written in January by Wisconsin Technology Council President Tom Still, who also served Thursday, March 9, as moderator of the panel discussion held in Whitewater, noted that the council is looking to create a “fund of funds,” proposing that the governor and the Legislature consider earmarking some $100 million from within the state’s $7.1 billion surplus for that purpose.

Within his commentary, Still described a public-private investment program called the Badger Fund of Funds, which, he wrote, was established by the governor and the Legislature in the mid-2010s, and serves as an umbrella for five early stage capital funds spread throughout the state. The fund, which was begun with $25 million, Still wrote, “spent the next few years matching” that amount “with twice the total in private dollars.” Investing began in the late 2010s and the fund, under rules set by the Legislature, can only invest in Wisconsin-based companies.

Funds within the Badger Fund of Funds include the Idea Fund of La Crosse, the Winnebago Seed Fund, the Gateway Capital Fund, the Winnow Fund, and the Rock River Fund.

Andy Walker, a partner with the Rock River Fund, was among panelist on March 9.

Within his commentary, Still wrote that the council is lobbying the Legislature for a larger fund of funds, writing: “More state investment in the early stage economy should be a part of the debate as lawmakers consider the next two-year state budget … to invest in larger increments than Badger was proposed two years ago.” He added: “The goal would be to attract more out-of-state investment and bigger rounds for emerging companies, an approach followed in some other states.”

A “round” is a term used to describe the investment process, during which funding is broken into specific stages, including “seed,” “Series A,” Series B” and “Series C.” Each round allows investors to gain equity or partial ownership of a company in exchange for capital.

A link to the full commentary written by Still in January is here: https://wisconsintechnologycouncil.com/insidewis-a-public-private-model-badger-fund-of-fund-is-performing-for-wisconsin/.

According to the Wisconsin Technology Council’s website, the TCIN is “dedicated to fostering innovation and entrepreneurship,” and works “in association with the Tech Council,” with “focus on the needs and challenges faced by new and growing technology-based businesses in Wisconsin.”

Joe Kremer, TCIN’s director, also was among panelists in Whitewater. He shared statistics about early stage investments made by venture capitalists in Wisconsin companies in 2022, which, he said, “will likely stand out as the state’s second-biggest year in dollar terms … exceeded only by the record year of 2021.”

Data shared by Kremer was developed by TCIN through information collected from various sources, he said. He cautioned luncheon attendees that the data was yet incomplete and would likely show larger gains as more information was gathered.

The panel also was joined by Whitewater area investor and First Citizens State Bank Chief Executive Officer Jim Caldwell, who was described by Still as having “a holding company that does some seed-stage investments.”

Caldwell said his saw his role more as an angel investor than venture capitalist.

Not just in Madison and Milwaukee

Within information provided by the Technology Council, Still was quoted as saying: “Investments by angel and venture capitalists don’t just occur in Madison and Milwaukee these days. We’re seeing interest statewide in early stage companies, especially in those regions where you might find a combination of talent, research and community support such as what exists in Whitewater.”

According to its website, Rock River Capital Partners describes itself as an organization that brings “a global perspective to the new Midwest opportunity through capital and connections to a global network.” Additionally noting that the company “exists to forward the ideas and hard work of the Midwest into great companies.”

Among those attending the luncheon were representatives from such institutions as the University of Wisconsin-Madison, UW-Whitewater, Merrill Lynch, Bank of American, Associated Bank, the Wisconsin Economic Development Corp. (WEDC), Walworth County Economic Development Alliance, Milwaukee Venture Partners, and WisPolitics.

Aided by a slide presentation titled: “Igniting Early State Investment — 2023 Wisconsin Portfolio,” Kremer noted that TCIN “provides services and resources to early stage investing and entrepreneurial communities, enumerating such concepts as deal flow, administration, education, networking events, and research.

TCIN does not operate a fund or make direct investments, he said.

“We are really in that middle, just trying to increase the supply of capital to all the entrepreneurs and trying to find creative ways to hook those two ends up between investors and entrepreneurs,” Kremer said.

Pointing to the Wisconsin portfolio methodology, he said TCIN derives its research from such sources as investor surveys; SEC Form D filings, which is a requirement for investors, governing private placements of securities; WEDC investment data, entrepreneurs, news articles and press releases, investor/entrepreneur conversations, and other online sources.

Kremer stated: “The portfolio is something that we’ve been doing every year for a long time. In fact, I was thinking, the first time we did this, I think, was ’08. Just under $100 million is what we tracked.”

Annual investment trends

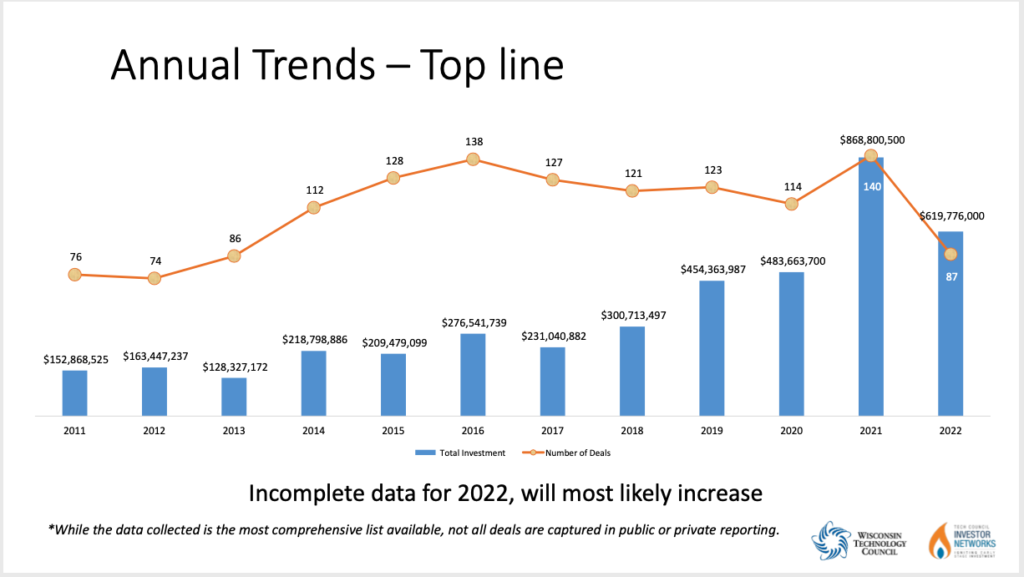

Sharing a graph reporting “annual trends,” which, he cautioned, had “incomplete data for 2022” and would likely, with more research, show trends with larger increases, he said that in 2011, across Wisconsin 76 “deals,” were made, bringing nearly $153 million in investment dollars to companies operating within the state. The number of deals climbed between 2013 and 2016 to 138, with approximately $276, million invested. Between 2017 and 2020, while the number of deals declined, reported at 114 in 2020, investment dollars rose to $484 million. The graph showed 2021 as a standout year, with deals climbing to 140, its highest number, bringing investment dollars of $869 million, also its highest number. In 2022, the graph noted 87 deals were made, bringing an investment of $620 million.

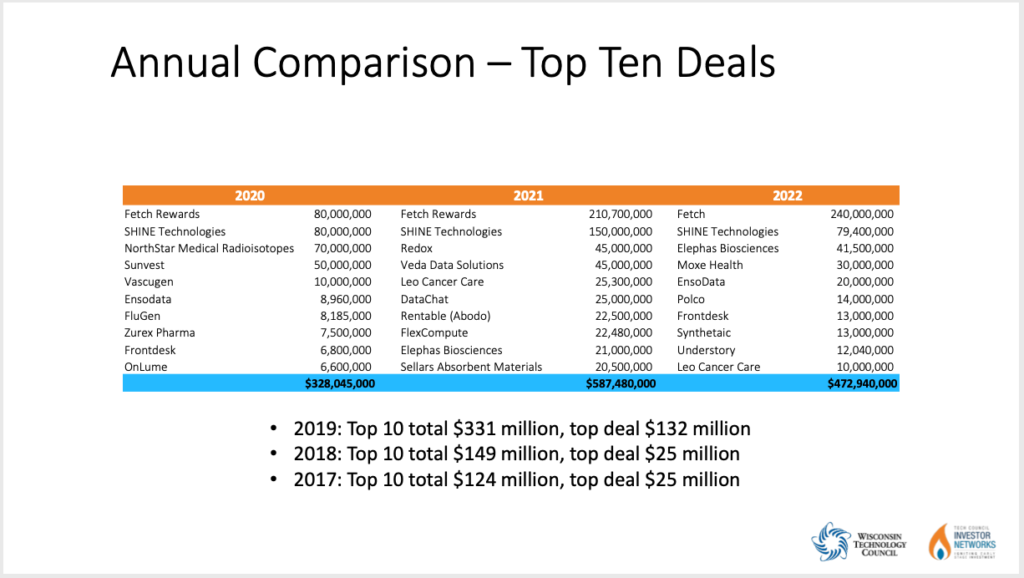

Looking more deeply into the numbers for 2022, he said: “We’ve seen $620 million in 87 deals, and that is coming from a whole different breadth of different companies all around the state, with a lot of differing, varying numbers around how much they are raising. From really small deals, I think our smallest is $25,000, to our largest, which was $240 million by Fetch (Rewards) last year. So we have really been doing an interesting job here, because if you look at where the overall numbers, these are the top 10 deals in Wisconsin for 2020, the top 10 deals raised just about $330 million. The following year, in ’21, there was about $580 million, and then this year (2022), it’s about $480 million, and we’re seeing this number continually grow, and that’s a real positive thing, because we are finding our entrepreneurs are graduating to larger and larger deals. They are bringing in larger rounds, like Fetch, at the $240 million (level). SHINE (Technologies) brought $80 million last year, Elephus (Biosciences) was at $40 million, and that’s a great thing.

“We want to see this continue to grow, because we really want to see a potential unicorn (a term meaning a startup company with a value of more than $1 billion) like Fetch, come up and grow, bring more money to the state, do more hiring, and really help our economy.”

Kremer said more venture capitalists from out of the state are starting to take an interest in Wisconsin-based businesses.

He added: “Back when we started the investor’s network, it was called the Wisconsin Angel Network … we had six investment firms in Wisconsin. We are up to 50. So in the last 20 years, there has just been a huge explosion, which is great. Now the story though, I do want to say, is we can’t take our foot off the pedal at this moment. We’ve got to keep pushing. Numbers are looking good. We’re having a great effect with all those programs that people have been working on around the state, but we can’t stop now. And so that’s one of the big reasons why we are pushing for a ‘fund of funds’ in our state, to bring more VC (venture capital) dollars.

Kremer next shared an annual comparison, highlighting “top ten deals,” in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

Making the list in 2022 were: Fetch Rewards, SHINE Technologies, Elephas Biosciences, Moxe Health, EnsoData, Polco, Frontdesk, Synthetaic, Understory, and Leo Cancer Care. Collectively, the top deals received investment funds in 2022 of $473 million.

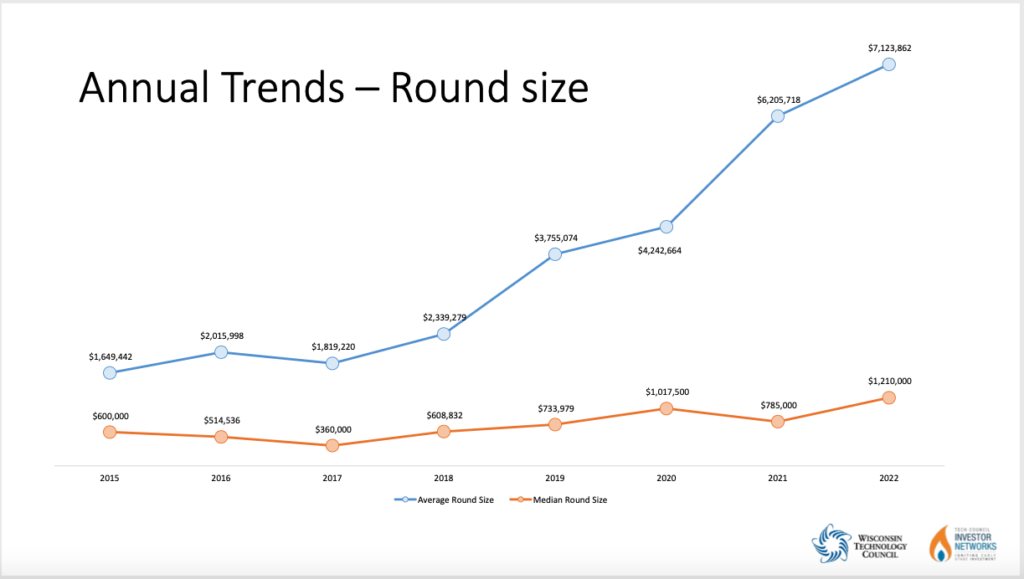

Another slide offered a graph showing the average- and median-sized round of investment funds received by deals between 2015 and 2022.

Average round sizes in 2015 were reported at $1.6 million, increasing over the years, with a slight dip in 2017 and again in 2020, to $7.1 million in 2022.

In 2015, the median round size was $600,000, advancing, with the same slight dip in 2017 and 2021, to $1.2 million.

Offering an explanation of the data, Kremer said: “This is just sort of an average, this is the mean and median size of deals. You can see the median, as we get those bigger and bigger deals, I mean if you are into stats just a little bit you know you have larger numbers at the top, and the median is going to keep going up, which it has been doing phenomenally. The thing that I really want to look at is the mean. What is the average investment round? Because we don’t want to see this get too high. Because the early companies that are just starting are going to have smaller rounds, so that if this starts creeping up too high, we are going to be seeing that a lot of the smaller companies aren’t bringing in those initial dollars.

“This graph tells like everything I need to know. Startups are getting the money at early stages and as they grow big, they are getting the larger rounds. So this is really good news for the state.”

Kremer said in Wisconsin, there is a “funding gap,” noting that for startups looking for rounds between $4 million and $10 million, “it’s almost a desert at times.” He added: “That’s a very hard rung to attract in this state at this moment. So that’s a big reason why we are pushing also for this fund of funds, so we can get some more early stage funds.”

Overall, he said, “numbers are looking fabulous.”

Deal making, success and risk

Next, Still introduced Walker, whom, he said, grew up in Stoughton and was involved as an investor through Rock River Capital at the ground level in the deal with Fetch Rewards.

Walker said a week after his fund put money into Fetch, the company’s executive officer quit, leaving Walker to run the company for six months, which, he said, he agreed to do in order to protect his investment.

“Then we encouraged some new investors to come in, and once we raised the first $4 million round then I exited the company,” Walker said.

Walker listed several other companies in which he invested, including a company that existed for 18 months, he said, before it grew to be worth $20 million and was sold to another company.

“It was a publicly traded company; it’s DXC now,” he said.

Additionally, he talked about a company which was funded by Drive Capital, which, he said, was the largest VC in the Midwest.

Walker said: “the company had four months of cash left and they asked me to step in … it was a great learning experience … we were able to sell the company to a private equity firm, but it was just a recovery of capital. We got everybody’s money back, but nobody made a return there.”

Walker talked about his experience working for the National Security Agency (NSA) where he learned about what he described as the “earlier version of data science.”

Walker said when he returned to Wisconsin, he noticed there were not employees available in the field of data science.

He worked with Marquette University to develop a program, describing the institution as “the first ones to jump on board, and I think they got other people to go.”

What’s happening in Whitewater?

Caldwell welcomed attendees to the Innovation Center.

“Being a Whitewater resident here, it’s wonderful to bring the Tech Council to our community and often times we think of Whitewater as the jewel that is kind of hidden. We’ve just got so many resources here at our fingertips that we’re so happy to really expose you to all of what we can do down here. We’ve got marketing, we’ve got legal, we’ve got accounting, we’ve got software, you know we’ve really got all of those supports,” he said.

He said a data science program was available through the UW-Whitewater business school, calling it “a huge success.”

Describing his holding company, Caldwell said: “Our involvement goes back to about the time this building was built … we noticed that, we got all of these supports and services here in this building, but we probably lack the gasoline, and that’s the money, the funding, to get these things launched. So it was with that thought in mind, we had a little excess of reserves in our parent company, holding company, and we said, well, maybe we can put some quiet, patient, we call it, capital into the mix here, and our scale of operation is, take about three zeros off, and that’s kind of where we’re at. We are kind of on the early, early stage — we really call ourselves angels, because … we are trying to take that initial — once the entrepreneur has got this idea, many times it’s funded with family, friends, mother-in-law, charge cards, whatever, so they bring the idea, and what we try to do is provide some capital to get that prototype done.”

Caldwell said his holding company typically offers seed money with rounds between $10,000 and $25,000.

Said Caldwell: “We use the Small Business Development Center (at UW-Whitewater) for feasibility kinds of things to get a little more understanding of the marketplace and so forth. We find that a lot of our time is coaching, quite frankly, because when you’re kind of coming out of the entrepreneurial program, even though you may have been in the business school and exposed to all of these things, the entrepreneur normally is quite focused on their idea and their project, and what we try to do is built a little bit into the business plan, kind of a PERT (Project Evaluation and Review Technique) chart to see how we can go from this stage to the next stage, put time frames in there, accomplishments, and try to put some discipline into the projects.”

What do angels do?

According to Still: “Most of the deals that we record, there are more deals that are angel than VC, by count, but the dollars (lean) heavily toward VC.”

Responding to a question posed by Still about the role in the marketplace played by angel investors, Kremer said: “I think what’s interesting is that we saw sort of a strain with the angel economy, because we didn’t have funds like Andy’s around. So they would make investments, and they would want to keep the investments rolling, so they had to go round after round. And it’s great now, as we are slowly building these early stage funds, that there’s a handoff. So we did build a really huge, really significant angel investment community. And that always created issues for some companies that were raising at $4 to $10 million, where that’s where you guys (VC investors) start coming in.”

Walker said his fund probably comes in earlier. He said one of his fund’s “best” deals “from a revenue perspective and just return on paper” was a Whitewater-based company.

“I do believe there was some local angel money that came into it. But a lot of this comes down to the size of the venture fund,” he said.

Walker described angel investors as providing a “smaller amount of money,” noting that “each check size is smaller, because you have to get at least 15 to 20 deals in a fund to kind of weather the storm. Assume a third go bankrupt, a third are going to do well, and a third you might get your money back. So to weather that, you need a nice portfolio.”

He said his fund holds $27 million.

“We write checks anywhere between $250,000 and $1.5 million, it just kind of depends on like the first round, it could be more in the middle, but when we talk about why it’s hard to raise $4 million rounds, and $10 million rounds, you would have to take Rock River Capital and make it a $250 million fund for us to be able to cover enough companies, 15-20 of them at those sorts of check sizes. So it doesn’t mean that we don’t participate in $4 million rounds, we do, but what we’ll do is roll out a $1.5 million check and we’ll set the terms, and then we spend a ton of time networking with venture capital firms around the country, and we have to encourage them to come into our deals. So it’s a back-and-forth like that,” he said.

He described the approach as “common,” saying that Rock River Capital did one deal on its own, adding: “and really wished we didn’t. What I’ve learned is if it goes really well, we’re going to need more money. If it goes really poorly, we’re going to need more money. So, I can’t really find a reason why I would want to do it myself.”

What types of companies are good prospects for VC funding?

Still asked Walker to describe the type of company for which he looks to become involved with funding.

Said Walker: “So this is the part that I think is really difficult to talk to people about, because there’s so many great companies out there, but the reality is only a small fraction are venture capital backable companies.”

For many companies, he said, a traditional financing arrangement through a bank is the best avenue for funding.

“For it to be a VC backable company, we’ve got to see a 10x return on our money. We’ve got to see market sizes that are just massive, because if you take a look at that — we’re going to lose … 100% of our money on the third, we’re going to lose some of our money on the next third, so the winners have got to be really big. Just for us to make — in general, our investors expect three times their money back. Whatever they put into our fund, they expect three times that back, so just think about how big our winners have to be if we kind of lost on the other ones.

“To be a venture backable company, essentially you have to be a company that can have massive scale and also be efficient with the capital. So companies that aren’t very efficient with capital are things like manufacturing and agriculture,” he said.

Walker said his wife’s family owns a manufacturing company which he described as a “very ‘CapEx’ heavy company.” The family invested $15 million in equipment, he said.

“A venture capital firm would never spend $15 million on equipment. It’s just not something that they do. So manufacturing and agriculture are very, very difficult to do as a VC backable company. Biotech, although it’s had some great returns, is also difficult, but it’s difficult for a different reason. Biotech is not capital efficient, which means it takes a lot of capital to achieve an outcome. To do that, you need a huge fund. So a $500 million biotech fund isn’t that big. Which is crazy, right? A lot of us think that sounds like a lot of money, but to truly do a biotech fund, I would want $1 billion to $2 billion to do it right,” he said, adding: “You have all the regulatory issues. But just the amount of capital it takes, to do things like any sort of therapeutic, it’s expensive.”

Walker said software companies are good candidates for VC funding because they are capital efficient. He described hardware companies as “ok,” but also “scary” because the process required building inventory and prototypes.

“There’s more there. So there are smaller segments that work for VC,” Walker said.

Citing opportunities in Whitewater, Caldwell said: “Following up on the software, most of our starts have been in more of the software. We don’t have engineering, we don’t have medical, so the ramp-up time is much shorter where you don’t have the clinical and all that you got to go through. The cost of startup is less, and probably the startup time is less.”

For more information about the Wisconsin Technology Council, visit its website: https://wisconsintechnologycouncil.com.

For more information about the Rock River Capital group, visit its website: https://www.rockrivercapital.com.

For more information about the Whitewater University Innovation Center, visit its website: https://whitewateruniversityinnovationcenter.org.

Madison-based Tech Council Innovation Network Director Joe Kremer, from left, First Citizens State Bank Chief Executive Officer and Whitewater resident Jim Caldwell, and Rock River Fund partner Andy Walker are panelists discussing statewide trends in early stage investing in Wisconsin. The panel assembled Thursday, March 9, at the Whitewater University Innovation Center to share stats, experiences and answer questions during a luncheon facilitated by the Wisconsin Technology Council, a nonprofit science and technology advisor to the governor and Legislature. The Wisconsin Technology Council is lobbying for $100 million to be placed in a venture capital “fund of funds” in response to the $7.1 billion dollar state surplus. Wisconsin Technology Council President Tom Still, not pictured, moderated the discussion. Kim McDarison photo.

This post has already been read 1653 times!