By Chris Spangler

Ed Karrels, whose career at Google has enabled him to give back generously to his hometown and other charitable endeavors, keynoted the Fort Atkinson Community Foundation’s 50th anniversary celebration Tuesday evening.

A 1992 Fort Atkinson High School graduate, Karrels earned a computer science degree at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh in 1997 and then went on to become the 56th employee at Google.

He first interned at Argonne National Lab in Chicago and then IBM in New York and Silicon Graphics in California. Working on the advertising system for Google from 1995-2005, he accumulated enough stock to sell and retire at age 30, when the company went public.

In 2011, he established a Fort Atkinson Community Foundation fund to provide scholarships encouraging students to enter the field of computer science. Two years later, his personal foundation gave $30,000 to create a computer lab at Fort Atkinson High School, which students named the Ed Karrels Digital Domain.

In addition, Karrels has supported scholarships and many other local projects through the foundation, such as the Fort Atkinson Wheels Park.

Addressing the approximately 100 attendees at Tuesday’s event, Karrels reviewed his career and several of the his foundation’s charitable efforts.

“When I graduated (from college), I moved out to Silicon Valley … My first job out there was at this company called Silicon Graphics. It was huge at the time; I’m sure you’re all familiar with it,” Karrels noted with humor.

“They made the coolest graphic machines — they did all the graphics for ‘Jurassic Park’ back in ’93 — and that’s pretty much when they peaked. It was all downhill from there,” he added, noting that after two years of layoffs, he followed a co-worker to work for a “friend of a friend” who was starting up an internet search engine.

“At that time, there were dozens of internet search engines,” Karrels said, noting that his friend told him, ‘It’s going to be huge. You should come join me.’”

He held off for a few months but then attended a Google party when the company got its first big venture capital funding.

“There were only 20 people altogether then,” he recalled, noting that when he signed on soon after, he was Google employee No. 56.

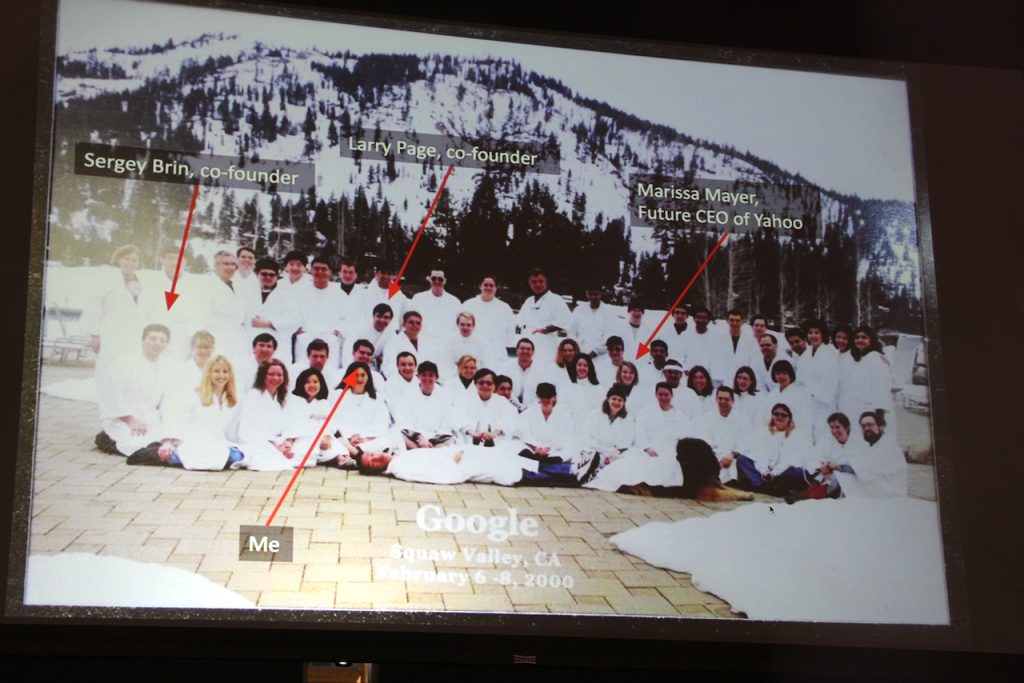

“A few months after I started, they took us all to Lake Tahoe to go skiing. This is a tradition; they did it once before. … First time, it was six people. This time, it was 70 people. Back then, the company was small enough that I could actually name everyone in the photo,” Karrels said.

At Google, he worked on the advertising system rather than the actual search engine.

“So we were the ones who actually made money and everyone else just (worked on) searches. The advertising team was very, very small. … I can say I wrote Version 1.0 of most of the Google ad system. I don’t know if my code is still in there,” Karrels said.

By 2022, Google’s ad business amounted to $225 billion, nearly 80 percent of the company’s total revenue.

“It was so successful, it’s being charged with being a monopoly now,” he said, referring to ad-tech antitrust charges by the European Commission.

Karrels started at Google in 1999, and in 2004, it went public.

“In case you wonder, going public also is called an IPO, initial public offering. When you start at a start-up, they’ll tell you what kind of salary that they are offering; they’ll also tell you you get X percent of the company …,” Karrels explained. “It’s worth nothing at the time until it’s publicly traded. Before that, it’s just funny money; we have these shares with a made-up value.”

The stock can not be sold until after the company’s IPO.

“The day you go public, it’s a party,” he said. “My friend and I went to the airfield at Oshkosh and bought airplanes.”

Karrels added, “So I retired at 30 years old and now I suddenly had a very comfortable bank account and a lot of spare time on my hands.”

He shared a story about an Italian professional bicycle racer who did not make much money until he entered the spotlight in 2003. That breakout year led to a renegotiated contract and all sorts of sponsorship deals.

“Suddenly he’s a star,” Karrels said. “I remember reading an article about him and his success. The interviewer talked to one of his teammates, and his teammate said, ‘You know, he’s always been a good dude, but you know what? After he became a star, whenever we’d out go to the pub, he’d always pay.’

“That made an impression on me. He suddenly has, through a lot of hard work and a bit of luck, an amazing windfall. And one of his first responsibilities is, ‘I should share the wealth. I must share it with my friends,’” Karrels said of the bicyclist. “And I really took it to heart.

“So I felt it was one of my responsibilities to spread the wealth wherever I can.”

He said that Google employees were given classes about long-term gains, stock shares and the alternative minimum tax.

“One of the interesting things was, even though we couldn’t sell the stock until it went public, we could give it away,” Karrels said.

And while the Google instructors talked a lot about taxes, they didn’t talk a lot about philanthropy. So Karrels hired a financial adviser who encouraged him to consider donor-advised funds.

“It’s like a tax-free bank account, where anything you put in, you get to write that off as a donation immediately, but you don’t have to spend it anywhere immediately,” Karrels explained. “You get to decide later what you’ll actually do with it, but the only thing you can do with it is donate it.”

It particularly is good for an appreciated asset, such as Google stock, especially considering that company’s revenue had grown more than 437,000% in five years to nearly $1 billion.

“So I took a bunch of my Google stock, put it in a donor-advised fund. I have this money set aside and all I can do is give it away. And it’s a lot of fun,” he said, adding that he suspects this “fantastic fund” will outlive him.

It was not long after that when St. Joseph’s Catholic Church and School moved to its Hackbarth Road location. During the process, the pipe organ counsel shorted out and caught on fire.

“I’m not a terribly religious person, but I love good music, particularly pipe organ music,” said Karrels, who had attended the parochial elementary school. “So I heard about this and asked, ‘Well, how much does a new pipe organ cost?’”

That marked his first gift using the donor-advised fund.

“It was an interesting opportunity that presented itself, and it got me thinking: ‘What kind of things should I be doing with this money?’ I figured opportunities like this will pop up, but I probably should think more strategic and long term,” Karrels recalled.

So in 2010, he established the Ed Karrels Continuing Music Performance Scholarship at UW-Oshkosh, where he had played trombone in various musical groups.

“I remember telling my high school band directors, ‘I’m going to study computer science for my career, but I’m going to also major in music just for fun,’” Karrels said.

However, juggling a double major was a lot of work.

“I dropped the major, but kept on playing, taking lessons, playing in bands, and I found that really rewarding,” he recalled.

Karrels said he enjoys music because it is fun and an interesting challenge, both physically and mentally.

“Mentally, you’re focusing on the music, trying to get the timing right and make sure you’ve got the right note breaks, make sure you’ve got your slide in the right position and you are listening around you. It’s not just hand-eye coordination; it’s hand-ear coordination,” he said.

“If you are a quarter of a second off, it’s the difference between the Chicago Symphony and the Fort Atkinson elementary school band,” Karrels continued. “It takes concentration.”

He said that while he is a fan of music, he doesn’t necessarily want to encourage students to major in music, since music can be a very tough career.

“We crafted this scholarship that said you have to be a non-music major, but still take lessons and play in an ensemble,” he said of the Ed Karrels Continuing Music Performance Scholarship.

There are 32 students in the program now, and Karrels tries to visit UW-Oshkosh each year to meet with the participants.

“They’re all talented in multiple areas and the professors say that every single one of these kids, who came in on audition (and) despite the fact that they’re not music majors, is a star in their ensemble,” he said.

The next scholarship Karrels established was in Fort Atkinson.

“I me with (teacher) Dean Johnson, and he was just starting out teaching computer science classes at Fort High. He said, ‘what I’d love to do is an advanced-placement course …,’” Karrels recalled.

However, he first needed to get more students interested in taking AP Computer Science.

“What can we do to encourage more kids to take the step? We could bribe them,” Karrels said. “So we decided to make a scholarship where the student takes the pre-requisite course and then the AP course and if they pass the AP exam, they get 1,000 bucks. And it worked.”

He continued: “I’m not trying to create more computer science majors, though that (would be) nice. I’m just trying to recruit more kids to give it a shot, learn a bit of programming. I think it is a generally useful skill.”

Since its inception, he has given the scholarship to 151 students, with 14 more who just passed the test on deck.

“I’ve been discussing this with a couple people this week and a thousand bucks today isn’t the same as a thousand bucks in 2010, so I think it’s time for a raise,” Karrels announced. “There’s been inflation, so … by next year, it’s going to be $2,000.”

The Fort Atkinson High School scholarship was followed by expanding the computer lab into the adjacent room, thanks to Karrels’ $30,000 gift.

He gave a shout out to Johnson and Tyler Sarbacker, the current computer science teacher, who have been the program’s boots on the ground.

“They’re the ones inspiring these students. I’m just the one bribing them to try to get themselves to school. So congratulations … on a fantastic program,” Karrels said.

He also mentioned that a side goal of these efforts is to get more women into computer science.

“They are drastically underrepresented,” Karrels said.

He estimated that Google’s workforce is 25-percent female, and while it can not hire based on gender, the company could recruit harder at women’s events. Another thing needed is for educators, parents and other advisers to retire the stereotype that deters females from studying math and science.

Karrels also has used his foundation to help the University of Illinois, where he was attending graduate school. He befriended an assistant marching band director who mentioned the poor state of the trombones.

“I was like, ‘do they need new trombones?’” Karrels said. “Well actually, I have that scholarship at UW-Oshkosh for non-music majors and most of these kids are not music majors. They just love playing in the marching band.”

It was the same at Illinois, so he bought new trombones for the Marching Illini.

Then, he heard a retiring tuba professor complaining about the condition of the tubas.

“So I bought a bunch of new tubas, got oddball sizes and a cimbasso, which looks like a trombone but sounds like a tuba,” Karrels said.

The Fort Atkinson native remarked that certainly, he could take his money and donate it to larger national charities such as the American Red Cross, but “projects like that are too diffuse. It’s hard to see whether there is even any impact.

“I feel like donating to my hometown and my alma mater,” he added. “I can have a direct result there. It’s not just a drop of water disappearing into an ocean. It’s going directly into the kids’ hands.”

Karrels and his wife, Nancy, also donate to the Experimental Aircraft Association’s Young Eagles program, which gives children free airplane rides, as well as mountain biking and hiking organizations and libraries.

“At Christmas, we sit down and discuss who we want to give our money to,” he said of his family. “It’s a lot of fun.”

In short, Karrels said, his philanthropy is divided into three types: tactical, strategic and fun.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, giving to food banks was a tactical situation as it provided much-needed help in the moment, he explained.

“You see a need, and here is something I can fix,” he said.

Strategic giving has long-term goals, such as investing in students. And the fun recipients are efforts that tickle their fancy, such as seeing-eye dogs or Fort Atkinson’s Wheels Park.

Karrels said that he is very appreciative of his good fortune and how it enables him to help support so many good causes.

“I love Fort Atkinson; it’s a great little town,” he said. “It’s got a healthy blend of business and recreation and is surrounded by lush landscaping that is uniquely Wisconsin. In the future, I hope all of you will continue to work with the community foundation to keep improving our town.

“I travel a lot, but I always will be a Wisconsin boy,” he concluded. “And my heart will always be in Fort Atkinson.”

A story about the Fort Atkinson Community Foundation’s 50th anniversary celebration, held Tuesday and during which Ed Karrels served as keynote speaker, is here: https://fortatkinsononline.com/fort-foundation-celebrates-50-years-of-giving/.

Ed Karrels, a 1992 Fort Atkinson High School graduate, shares slides as he talks about his life and career. Karrels served as the keynote speaker at the Fort Atkinson Community Foundation’s 50th anniversary gathering Tuesday. He was the 56th employee hired by Google, retiring at age 30 when the search engine went public.

Ed Karrels, serving as keynote speaker at the Fort Atkinson Community Foundation’s 50th anniversary gathering Tuesday, shares a slide from 2000, depicting the early Google crew of which he was a member. Among those pictured, as indicated within the slide, are Sergey Brin, co-founder, along with Larry Page, of Google, and Marissa Mayer, whom the slide identifies as a “future CEO of Yahoo.”

Ed Karrels, serving as keynote speaker Tuesday during the Fort Atkinson Community Foundation’s 50th anniversary celebration, shares a slide depicting him in a newly purchased airplane. The Fort Atkinson High School graduate and former Google employee, describing himself as the 56th person employed by Google, enjoyed taking youngsters on flights, he said. His groundbreaking endeavors allowed Karrels to retire at the age of 30. He has since engaged in philanthropic giving.

Fort Atkinson Community Foundation 50th anniversary celebration keynote speaker Ed Karrels shares a moment with his mother, Connie Thomas, Fort Atkinson.

Chris Spangler photos.

This post has already been read 5358 times!