By Kim McDarison

Voters heading to the polls this April will find an operational referendum question posed by the School District of Fort Atkinson.

This year, the district is asking taxpayers to allow it to exceed its state-imposed revenue cap for operating expenses by $6.5 million for each year in a three-year period, beginning with the 2024-25 school year.

The ask is for a nonrecurring referendum, which, School District of Fort Atkinson Board of Education President Kory Knickrehm, responding to questions in a recent interview, noted, means that it will sunset after the three-year period.

According to district literature, resources previously approved by taxpayers for operational spending above the state-imposed revenue cap, in part, expired last year.

Director of Business Services Nathan Knitt noted that the last operational referendum approved by the voters came with two components: one recurring, in the amount of $2.25 million, which was included in the 2020-21 school year, and one nonrecurring, in the amount of $3 million. While the recurring portion was approved for perpetuity, the nonrecurring potion expired in 2023.

Knitt joined the district as its director of business services in July. His predecessor, Jason Demerath resigned last March, having accepted a position as executive director of financial services with Wisconsin’s CESA-2. His last day of work within the district was June 30, 2023.

During the 2022-23 school year, the district placed an operational referendum question on the 2022 spring ballot, which did not meet with voter approval.

On Nov. 8, 2022, the district’s voters approved through referendum a capital expenditure of $22 million to be used to build secure entries at the district’s six schools, along with other maintenance needs, such as roofing, plumbing, and electrical, as well as to address traffic flow at the high school. An operational referendum question placed on the same ballot, asking voters to approve a $3 million recurring component and a $4 million nonrecurring component for 2023-24 and 2024-25, and $5 million nonrecurring component in the 2025-26 school year, failed.

Last school year, the district laid off members of its teaching staff to accommodate the absence of the requested funds.

In this, the 2023-24 school year, the district prepaid $7 million in debt, which, district literature states, allowed the district to “maintain a stable tax rate,” which Knitt, in a recent interview, said is one of the district’s priorities. A stable tax rate is desirable, Knitt noted, when the state, looks at general state aid allocations each year and distributes funds across Wisconsin’s 421 school districts. The amount of monies spent in previous years by each district affects the amount distributed by the state annually, he explained.

Knickrehm said that even through last year’s operational referendum question failed, the district’s taxpayers over the years have been very supportive of their children’s schools.

He said five operational referendums have in past years been approved by the district’s taxpayers, adding: “We have had a lot of support.”

Looking at past referendums which received voter approval, he listed a five-year operational referendum approved in 2006, and four three-year operational referendums approved in 2011, 2014, 2016, and 2020.

Two three-year operational referendum questions, posed in 2022 and 2023, failed, he said.

In 2022, the district’s voters approved a capital referendum of $22 million to be used to address security and maintenance needs.

Knitt said the district took out a loan for $22 million to pay for such work as doors, security, and roofing, which has been completed at the middle and high schools. Similar work will commence at the district’s elementary schools this summer.

Why does the district need operational referendums?

In January, 2023, then-Fort Atkinson Director of Business Services Jason Demerath, offering a presentation to the district’s board of education, responded to this question: Why does the district need to consider an operational referendum?

He said that the answer revolved around the district’s previously approved $3 million operational referendum, which was approved by the voters in 2020, and would sunset in 2023.

That, he said, coupled with the district’s unsuccessful ask of the voters for an operational referendum in November of 2022, the district’s declining enrollment, the “lack of any state allowable revenue increases,” and the then upcoming loss of one-time COVID-19-related federal funding, while the district simultaneously faced inflationary impacts and an increasingly competitive labor market, created a condition which he described as a “looming fiscal cliff.”

Demerath said funds achieved through a successful operational referendum question were required to meet the district’s strategic goals and service the community.

Both Knitt and Knickrehm said recently that the same conditions outlined by Demerath in January of 2023 continue to prevail.

Additionally, Knickrehm said: “It’s not a Fort Atkinson thing.” He noted that referendums are being sought by school districts across the state.

Of school board members and district officials, he said: “We don’t want to do them (referendums) either. It takes a lot of time. We want to get back to educating children, and we’ve done a dang great job.”

He cited improvements in test scores as evidenced on the last set of Department of Public Instruction (DPI) school report cards.

He noted that the high school “has some work to do, but that will blossom quickly.”

He added: “We are proud of our results.”

An earlier story about DPI school report cards and scores earned by the district is here: https://fortatkinsononline.com/dpi-releases-2022-23-district-school-report-cards/.

An earlier story outlining strategic goals associated with school report card data is here: https://fortatkinsononline.com/abbott-relates-dpi-school-report-card-data-to-the-districts-strategic-plan/.

An earlier story, offering in January a recap of achievements described by the superintendent as ‘community distinction,’ is here: https://fortatkinsononline.com/school-board-receives-strategic-plan-update-with-focus-on-community-distinction/.

Cost of instruction

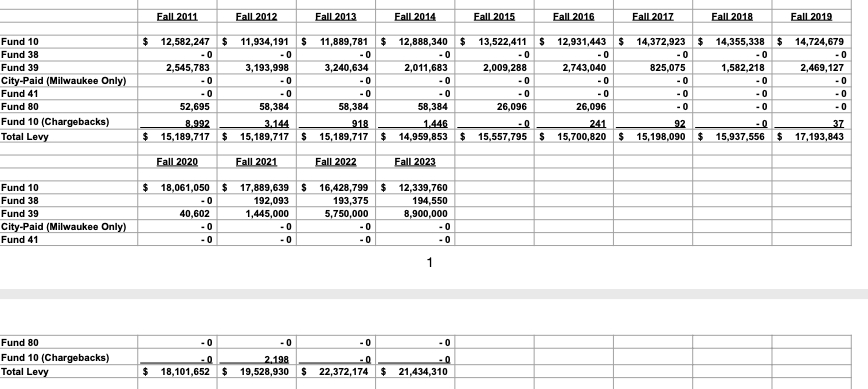

During a recent interview, Knitt shared a DPI spreadsheet showing the district’s taxpayer-supported levy and associated state-imposed levy limits between 1993 and 2023.

The Fort Atkinson School District total tax levy for the 2023-24 school year is $21,434,310.

The spreadsheet shows that the levy has risen from $9.1 million, collected from taxpayers in 1993, to $21,4 million, collected in the fall of 2023.

Over the last five years, the levy is as follows: 2019, $17.2 million; 2020, $18.1 million; 2021, $19.5 million; 2022, $22.4 million, and, showing a slight decline from the previous year, 2023, $21.4 million.

The chart also shows the state-imposed revenue levy limits for each year, with the last five years as follows: 2019, $14.7 million; 2020, $18 million; 2021, $18 million, 2022, $16.6 million, and 2023, $12.5 million.

The spreadsheet above, as produced by DPI and shared by Knitt, shows a portion of the data associated with the School District of Fort Atkinson’s levies and levy limits between the fall of 2011 and 2023. The full spreadsheet is found here: http://fortatkinsononline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Fort-Atkinson-Tax-Levy-History-Multi-Year-Levies.pdf.

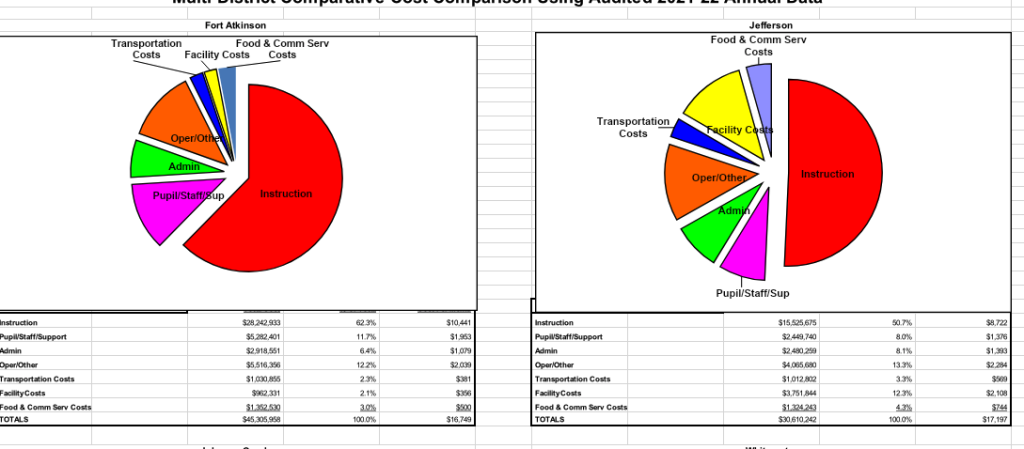

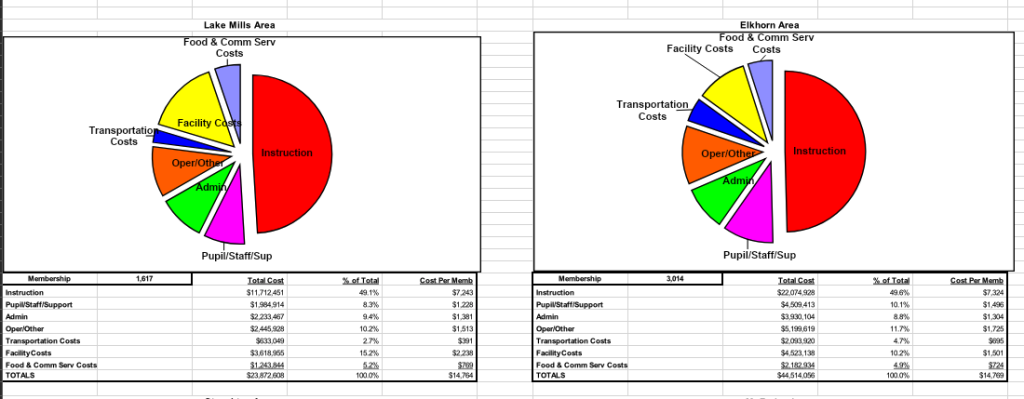

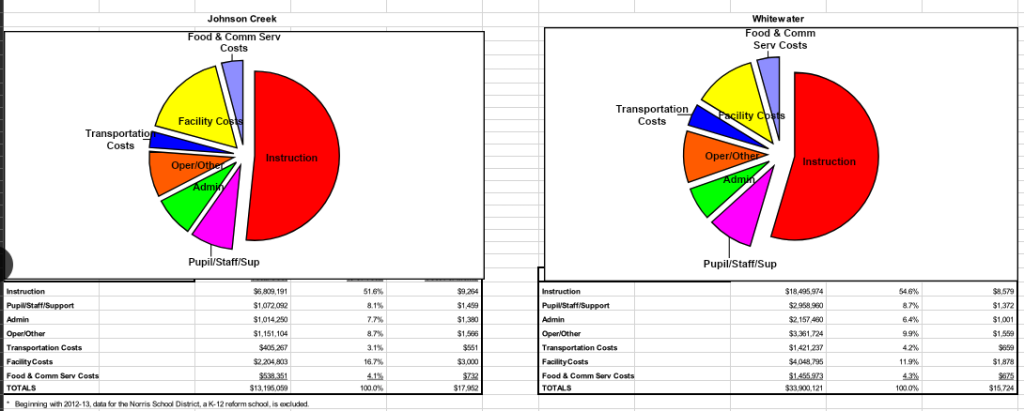

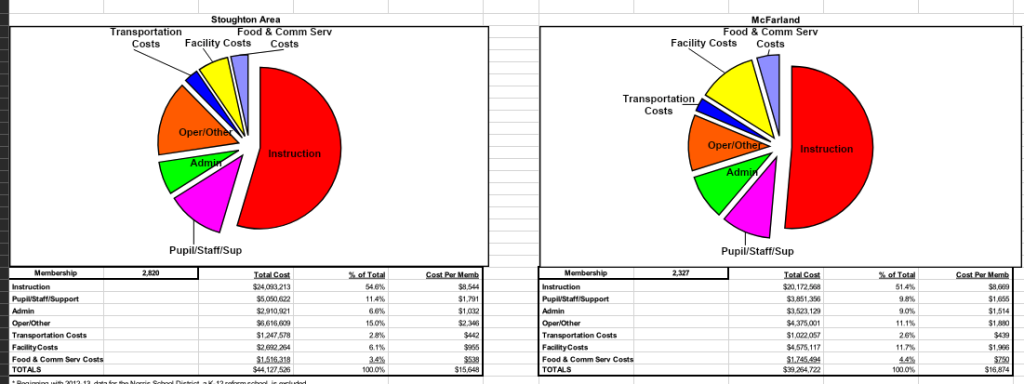

Sharing “cost per member” comparative charts from the DPI website, shown above, Knitt said that the School District of Fort Atkinson’s allocation of spending falls “right in line” with other districts in Jefferson County.

“We are right in the middle of spending in Jefferson County,” he said.

“After looking at the comparables within the Badger Conference and Jefferson County, it’s looking like we are in the middle ground. We are on par,” Knickrehm, said, but, he noted, “if it (referendum) doesn’t pass, that changes everything. Right now, our spending is right in line with everyone else.”

Knitt said that the School District of Fort Atkinson, according to the DPI website, is spending on average, as reported in 2022, some $16,749 per student. He said the most recent numbers available on the DPI website for comparison purposes are from the 2021-22 school year.

He offered pie charts showing eight comparable districts, including, along with Fort Atkinson, those of Jefferson, Johnson Creek, Whitewater, Lake Mills Area, Elkhorn Area, Stoughton Area and McFarland.

Cost per member within each district in the 2021-22 school year was as follows: Fort Atkinson, $16,749; Jefferson, $17,197; Johnson Creek, $17,952; Whitewater, $15,724; Lake Mills Area, $14,764; Elkhorn Area, $14,769; Stoughton Area, $15,648, and McFarland, $16,874.

A larger view of the full spreadsheet is here: http://fortatkinsononline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/8-District-Comparables-to-fort-.pdf.

The state’s voucher program and district resources

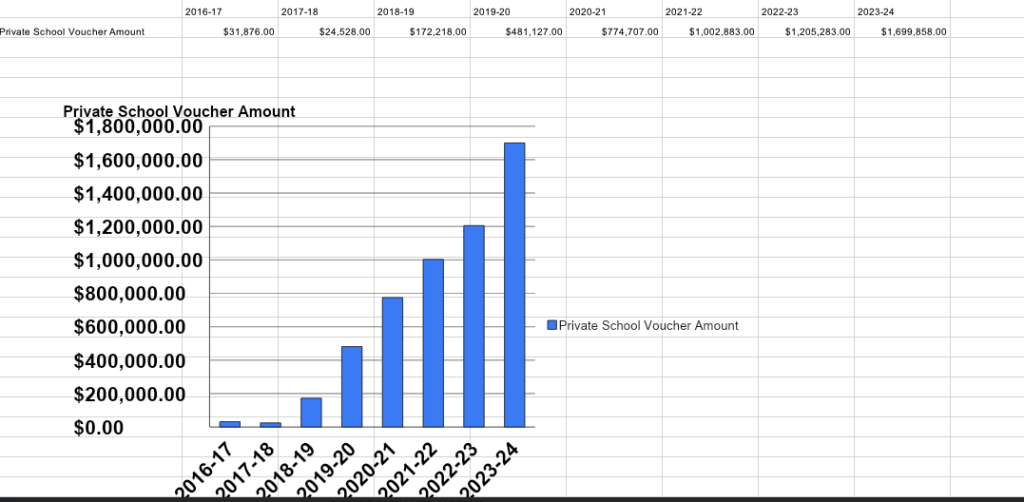

Knitt — responding to questions and addressing the impact of the state’s voucher program as it relates to public school financing — said that the state’s current practices are designed to increase funding for the voucher program.

In the 2022-23 school year, the district levied $1.2 million in property taxes that were used to fund the voucher program.

“The district collects that money, but then it instantly goes out the door to the voucher schools,” Knitt said.

Knickrehm noted that students who live within the district, but opt to attend private schools, still remain the responsibility of the district when it comes to their overall education.

“We get zero dollars for that,” he said.

Said Knitt: “We are partners with the private schools, especially when it comes to students with special needs.”

He additionally described extracurricular activities provided by the district and offered to students living within the district, as part of the district’s responsibility when partnering with private schools.

The responsibility extends to any school in the state or parents using online resources. If the child resides in the district, then the district remains responsible for ensuring the quality of the child’s education, both Knitt and Knickrehm said.

Knickrehm noted that not every school a child might attend is receiving voucher assistance through the state’s program.

Within the city of Fort Atkinson, he said, St. Joseph school is not enrolled within the state’s voucher program, so those students do not receive monies through the program. Other schools, including Crown of Life and St. Paul’s Lutheran School, do.

Still, he said, the district remains responsible for making sure all of those students receive access to a full education, so they make use of district amenities. He cited band and extracurriculars as examples of amenities used by children within the district attending private schools.

“We are responsible for the education of those kids, so if St. Joe’s has a kid that needs services that they can’t provide, we are responsible,” he added.

Knitt noted that there is some federal funding available to help offset costs. He named the IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) grant, and other special education grant opportunities. But, he said, for those schools electing to use those funds, the School District of Fort Atkinson partners with them to make sure they are filling the requirements of special and low income status.

According to the DPI website, IDEA funds may be used for staffing, educational materials, equipment, and other costs to provide special education and related services, as well as supplementary aids and services, to children with disabilities.

Knitt said that services provided by the district to private schools might include those of a speech and language pathologist.

For students requiring those services, he said, the district sends one of its teachers to the child’s school.

“We get a little money to bear that cost, but we bear the brunt of it,” Knitt said.

He added: “We don’t really know how many kids are enrolled in private schools. We get an estimated voucher number from the state in the fall.”

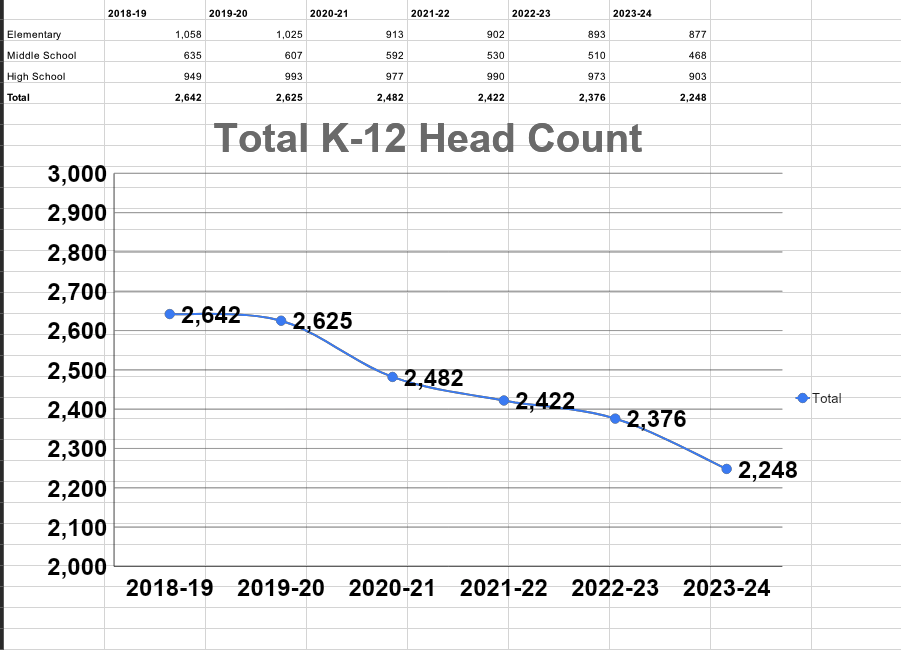

Knickrehm said that some of the district’s declines in enrollment fall in line with additional educational opportunities moving into the area.

But, he noted, the decline in enrollment does not always correlate proportionately with the district’s expenses.

As an example, he said, “if hypothetically, there has been a 10% decrease in enrollment, we can’t just cut teachers proportionally. We can’t cut 10% of staff.”

Further, Knitt said, “the amount the state is allocating to its voucher program is going up, but that does not mean we are losing kids.

“How the state breaks down the voucher funds went up; K-8 voucher (allocations) went up by 17% last year, and for high school students, it went up by 37%. The state has given the voucher program a massive increase,” Knitt said.

Meanwhile, he said, the full state budget received a 3% per pupil increase.

Still, he cautioned, “I don’t want to make this a school voucher referendum. If we are spending $17,000 (per student) in public school and $12,000 in private, it’s not an apples-to-apples comparison.”

A bar graph shared by Knitt from the DPI’s “Private School Voucher History Workbook,” shown above, highlights the cost associated with the voucher program. The graph shows that the amount per student that is associated with the voucher has increased substantially over time, Knitt said.

A graph, supplied by Knitt and shown above, shows the district’s total K-12 headcount between the 2018-19 school year and the 2023-24 school year. The count of all students in the district is taken on the third Friday in September.

What about inflation?

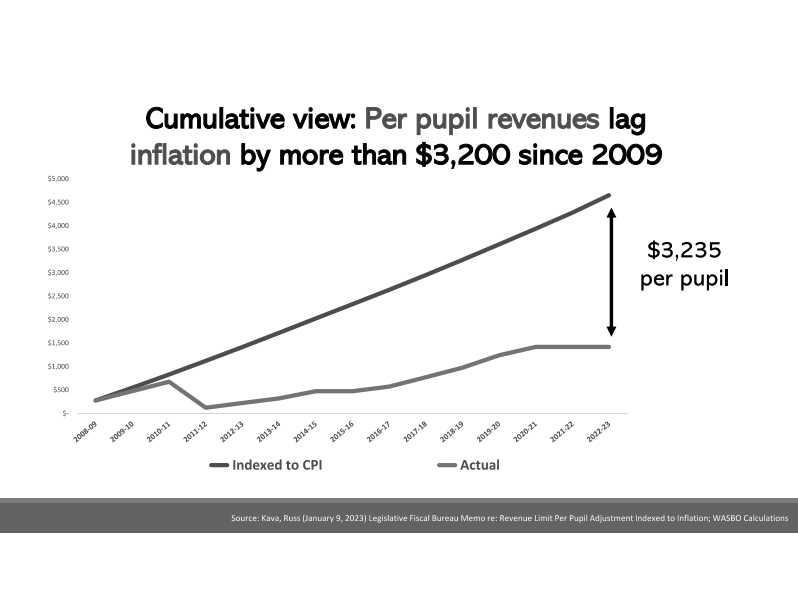

Knitt said that inflation was reported at 8% last year. The district is given its inflation index by the state. This year, it is reported at more than 4%.

“But the biggest piece is the amount we are allowed to tax, and state aid, which is not keeping up with inflation, and hasn’t for going back to the 2009-2010 school year,” he said.

When the state was experiencing 8% inflation, our increase in state aid was zero, but we paid our teachers 4% more, Knitt said.

Said Knickrehn: “We had to or we would be at risk of losing teachers to other districts. We had to keep up with inflation.”

Knitt said teachers are allowed to negotiate up to inflation.

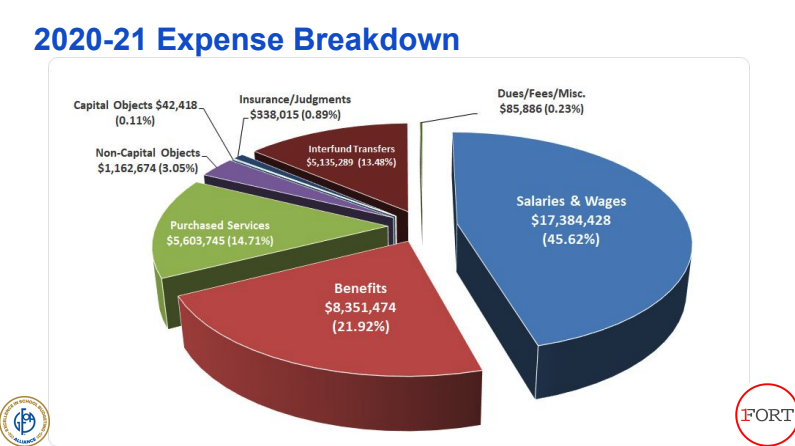

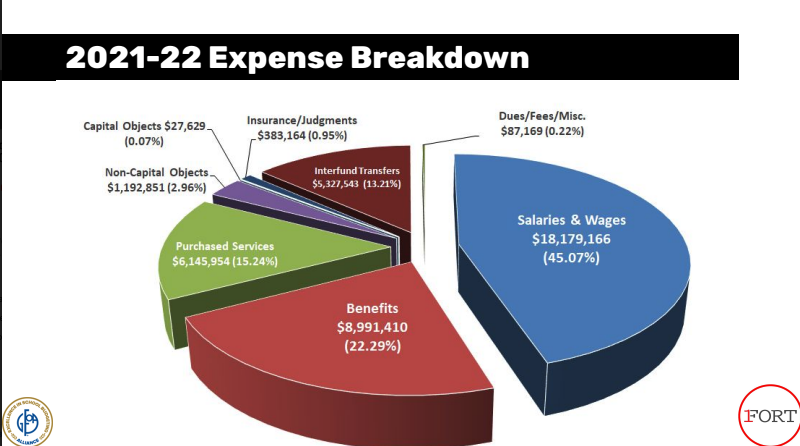

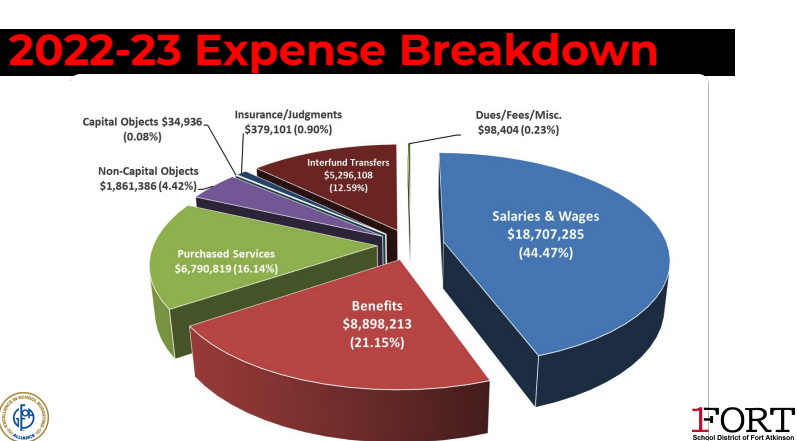

Three pie charts above, as shared by Knitt, show a breakdown of the district’s expenses, during the 2020-21, 2021-22 and 2022-23 school years, respectively. Both Knitt and Knickrehm, in a recent interview, said about 80% of the district’s budget is used to support salaries and benefits. When looking at the charts, Knitt said: “One note I want to highlight is that the Interfund Transfer category is all staffing expenses. By accounting standards we need to account for Special Education staff in a separate category. This does come out of the General Operating Budget, but when we say 80% of our costs are people, this is part of that 80%.”

The graph above, produced by the Wisconsin Association of School Business Officials (WASBO), highlights, according to Knitt, “how the state has not kept up with spending as inflation has gone up over time. The state historically linked increases in education funding to CPI (Consumer Price Index), but stopped matching increases to inflation in 2009. Had the state kept up funding levels to match inflation, we would not need to go to referendum.”

Tax rate and tax stabilization

Said Knickrehm: “We have lowered our tax rate.”

According to district literature, the school board recently lowered the property tax levy rate by $1.31 for the 2023-24 school year to $9.61, which it notes, is a 12.21% decrease. Literature further states that the rate “is the lowest mill rate in a decade for the School District of Fort Atkinson.”

The literature additionally notes that “an approved operational referendum would not increase the property tax rate of $9.61 per $1,000 of assessed property value.”

When looking at the overall tax levy for homeowners within the district, Knickrehm said, the district’s portion is not going up.

Knitt additionally talked about the district’s use of debt defeasance, saying: “We paid $3.4 million over the life of a loan in interest. He cited a loan used to fund the district’s $22 million capital improvement referendum approved by the voters in 2022.

“So the debt is paid down,” he said.

Responding to some residents who have asserted that if they do not approve the referendum the tax mill rate will go down, Knitt said the argument was not wrong — “the mill rate will drop,” but, he said, only for a year.

Additionally, he said, the state’s formula used to award general aid looks at the spending within each of the state’s 421 districts, and allocates monies “based on spending per member.”

Said Knitt: “If you have massive fluctuations — when the state divides up its general aid, what the district gets is based on spending per member of all the 421 districts in the state. So if your spending goes down, you get less.

“So next year’s mill rate will come back,” he said, based on receiving less state aid, “because we weren’t spending as much.”

From a fiscal standpoint, he advised, it is more judicious to approve the referendum, and achieve a stable tax rate, avoiding “giant swings,” to avoid the unpredictability in changes in general state aid.

Knickrehm agreed, noting that lowering the tax rate by not approving the referendum might look beneficial to some, but, he said, “It’s beneficial for a year, but there are a lot of moving pieces that makes projections subject to change. It is dependent on what every other school district in the state is doing.”

“With state aid,” Knitt said, “we get an estimate from the state in July, and we are given a final notice on Oct. 15, and the board sets the levy anywhere from Oct. 15 to 31.”

What happens without the referendum dollars requested?

With no new referendum dollars, Knickrehm said, there would be more cuts.

About 80% of the district’s budget is used to fund salaries and benefits, he said, “so reductions there will make the biggest difference, because the rest of the pie is 20%. So that means a reduction in teachers and staff.”

Last year, to adjust for the voters’ decision not to approve the referendum, among all staff members, 43-45 FTE or full-time equivalents, were cut, Knickrehm and Knitt said.

Looking at the prospects of more reductions and cuts in spending, would voters fail to approve an operational referendum in April, Knickrehm said: “From where would they come? I’m speculating because it’s up to the board, but it could come in programs, staff layoffs, things that make Fort proud.”

Where does it end?

Said Knickrehm: “85% of (Wisconsin’s) schools are going to operational referendums. This isn’t going to end. The chance that we are going to come back in three years is high.”

Said Knitt: “The lack on the part of the state with keeping up with inflation, that’s part of what’s driving referendums, and keeping up with student needs.”

As stated on district literature, districts, like Fort Atkinson, face financial challenges due to “a lack of funding for public education from the state Legislature in recent years.”

While inflation may be going down, the state still is not providing funds to address the inflation gaps that accrued in previous years, nor is it providing funds to address current inflation rates, Knitt said.

The district’s literature points to “rapidly increasing expenditures and expenses,” as another cause of financial challenges.

Addressing student needs, Knickrehm said: “Students need more supports; we are adding supports in math and reading, and students need that kind of help.”

“Tied in with the cost of inflation, there are students with special needs who require one-on-one aides, which comes with a cost, and we have costs associated with, for example, mental health,” Knitt said. He added: “When I was in school, we didn’t have school psychologists, and speech and language pathologists in the buildings, but kids need it. They probably always needed it, but we just didn’t have it in the schools.

“It’s never been harder to be a kid than in today’s society. There is social media and cell phones, so kids are becoming more aware of everything in the world as a whole, and families are struggling to keep up with inflation, the cost of living, parents are stressed and they are trying to make ends meet.”

School literature associated with the referendum cites “the state’s outdated school funding formula as a contributing component to school financial challenges.

Knickrehm noted that even under such prevailing circumstances, “we have to be prepared to learn everyday, so that means not being distracted in the class. We know that kids learn best when we meet them where they are at. We have to education that child no matter what. This is about children within our school district.”

Some referendum history

School referendums, both operational and capital, in recent years have been a topic of discussion across the state and within the School District of Fort Atkinson.

2021

In June, 2021, the district, through use of a 28-member Facilities Advisory Committee (FAC), identified three $100-plus school building improvement options to bring before the school board for its consideration.

Plunkett Raysich Architects (PRA) representative Nick Kent, who participated in the process, told those attending a Zoom platform FAC meeting that the goal of the FAC was to produce a long-range master plan for the buildings operated by the School District of Fort Atkinson.

“The FAC will identify viable facility solutions to present to the community for feedback, which will be narrowed through community engagement sessions, with the final options being tested via a community-wide survey,” Kent said.

The committee held its first meeting in September of 2019, charged with the task of exploring both long- and short-term solutions to maintenance issues and other facility needs as identified that spring within a deferred maintenance report completed by educational facility consultants CG Schmidt (CGS) and PRA.

The committee held eight monthly meetings over a period of 20 months — including a 14-month pause observed during the COVID-19 pandemic — during which time PRA shared 10 options designed to improve the conditions of the district’s buildings and better position them to support models of modern learning and future growth.

Options came with estimated price tags ranging between $36 million, addressing issues of maintenance only, and $133 million, which included costs associated with replacing the district’s existing elementary and middle school buildings with two new facilities each designed to serve students in grades 4K-8.

An earlier story about the advisory committee and its work is here: https://fortatkinsononline.com/three-100-million-plus-school-building-improvement-options-to-be-presented/.

In December, 2021, the board was presented with data collected by the Milwaukee-based Donovan Group, the organization hired by the district to create and facilitate a district needs community survey. The survey was made available to community members online that November.

Two representatives from Donovan Group, including its president and founder Joe Donovan and the organization’s Lead Survey Strategist Perry Hibner were in attendance during the board’s Dec. 13, 2021 meeting.

A presentation about the survey and its results was given by Donovan as an addendum to a presentation given by School District of Fort Atkinson Superintendent Rob Abbott, who spoke about achievements made by the district as it worked towards goals set forth in the district’s strategic plan. Future plans to address the district’s identified facilities needs were cited as a component of one of the district’s strategic plan’s goals, Abbott said, which addressed the district’s desire to create “an inclusive culture of growth and being responsive to our learner and community needs.”

Abbott’s update, outlining strategic plan goals and achievements, is here: https://fortatkinsononline.com/school-district-strategic-plan-update-shared/.

Facilities needs as identified by the district included their accessibility, status and safety, Abbott said.

During his presentation, Donovan noted that his company had worked with the district in 2019, at which time it helped facilitate a similar survey, designed to learn from stakeholders their thoughts about supporting an operational referendum. The more recent survey, he said, focused on two referendums, one operational and another for facilities improvements.

“The purpose of the survey was to gather feedback from community members to evaluate solutions that meet the community’s needs, are financially responsible, and move the district and community forward. The district also aimed to gauge the community’s support for a potential operational referendum,” he said.

Of the 998 survey respondents, Donovan said that 75% believed that the district “should address needs now.”

An earlier story about the survey conducted by Donovan Group is here: https://fortatkinsononline.com/school-survey-data-released-75-of-respondents-say-district-should-address-needs-now/.

2022

Information shared by Demerath during a school board meeting held in June, 2022, indicated that the district would likely be seeking a $22 million referendum for capital improvements funding and an operational referendum as follows: a four-year recurring referendum of $2.7 million, a $4.4 million nonrecurring referendum in the 2023-24 and 2024-25 school years, and a $5.5 million nonrecurring referendum in the 2025-26 school year.

Demerath said that improvements to the district’s facilities — as a result of an aggressive program in place to pay down capital debt — could be achieved through referendum dollars without increasing the district’s tax rate.

A story about the district’s capital improvement plans, as outlined in 2022, is here: https://fortatkinsononline.com/fort-school-board-learns-details-regarding-proposed-november-ballot-referendums/.

Also in June, 2022, the board learned the results of a survey conducted by Donovan Group.

The organization had facilitated two surveys revolving around facility-based and operational needs of the district.

Referendum questions to address both operational and capital needs were being considered by the board for potential placement on the November, 2022, ballot.

Results presented by members of the Donovan Group were collected through a survey made available to the community in May, 2022.

Information presented, as determined by the May survey, indicated that voters within the district gave priority to funding facility projects in the following order: urgent elementary maintenance, secured entrances at buildings, and building a new middle school.

Addressing the board in advance of the presentation of the survey results, Abbott noted that the survey focused on the buildings within the district and their “accessibility, status and safety.”

Said Abbott: “In November of 2021, the School District of Fort Atkinson asked voters to participate in a community survey to evaluate the district’s financial and facility needs and then to consider possible solutions … Understanding that much has changed over the past several months, in May (of 2022), we again asked residents to complete a followup survey to provide additional input on how much things had changed since we had polled our public back in November.

Addressing the board, Hibner, Donovan Group, produced a series of slides, titled: “Operations and Facility Community Survey Report,” showing survey responses as collected from over 1,000 members of the district in May.

Hibner encouraged the board to “trust your data.”

He called the survey results “encouraging.”

“It was fantastic to see more than 1,000 residents complete the survey. It represents more than 38% of your K-12 student population,” he said.

An earlier story about the districtwide survey conducted in May, June, 2022, is here: https://fortatkinsononline.com/school-district-survey-shows-community-support-for-funding-elementary-school-maintenance/.

In October of 2022, in advance of the November election, and according to information released by the district, a referendum question, with two components, would ask voters to approve funding for operational expenses.

Within its first component, the question asked voters to approve a funding increase not to exceed $3 million annually on a recurring basis, meaning the district would be granted the authority to exceed the state-imposed revenue cap by $3 million in perpetuity, beginning with the 2022-23 school year.

A second component of the question asked voters to approve additional funds over the revenue cap on a nonrecurring basis, meaning that the increase would be in effect for a specific period of time, in this case, three years. The question asked voters for nonrecurring increases as follows: in 2023-24, an amount not to exceed $4 million; in 2024-25, an amount not to exceed $4 million, and in 2025-26, an amount not to exceed $5 million.

Answering question by phone in October, 2022, Demerath said that approval of the operational referendum question would have a combined effect, allowing the district to exceed the state-imposed revenue cap by both the recurring and nonrecurring amounts in each year that the nonrecurring amounts applied. In 2023-24, the combined extension would result in the district’s ability to exceed the revue cap by $7 million; in 2024-25, the district would be able to exceed the cap by a combined total of $7 million, and in 2025-26, the district would be able to exceed the cap by a combined total of $8 million, after which time the nonrecurring component of the referendum would sunset. In subsequent years, unless a new nonrecurring referendum question would receive voter approval, the district would be allowed to continue to exceed its cap annually by $3 million.

An earlier story about the referendum questions, which were placed on the November, 2022, ballot is here (pie graphs showing the districts revenues and expenses are included in this story): https://fortatkinsononline.com/fort-school-district-shares-budget-four-referendum-outcomes/.

In November, 2022, voters approved a $22 million capital referendum, but voted down the proposed operational referendum.

Responding to the November, 2022, election results in a letter published in Fort Atkinson Online, Knickrehm wrote: “As a board, we will continue fostering conversations with community members about the future of our local schools.”

After the results of the November, 2022, election regarding the referendum were announced, Knickrehm wrote, several residents asked: “Now what?”

He wrote: “The simple answer is that the needs of our schools will not go away. Therefore, we must return to the drawing board and develop a new solution that meets the needs of our students and our communities. Because of the urgency of the situation, this work will begin immediately and we will be looking at coming back in April (2023) with a solution on the ballot.”

2023

In January of 2023, Demerath told the district’s board of education members that asking the district’s taxpayers to again consider an operational referendum would allow the district to achieve the necessary funds to meet the district’s strategic goals and service the community.

That same month, the board approved a two-part $8 million operational referendum question for placement on the April 4, 2023, general election ballot.

Board members approved “Option A,” one of two options presented which, as outlined by Demerath, would have allowed the district to collect from its taxpayers $3 million on a recurring basis beginning in the 2023-24 school year and $5 million on a nonrecurring basis for each year within a four-year period, beginning with the 2023-24 school year and ending with the 2026-27 school year, for a total of $8 million above the state-imposed revenue cap in each of the four school years.

Demerath offered several slides during a school board meeting, illustrating the district’s need for an operational referendum.

Sharing a slide titled: “Total K-12 Head Count,” Demerath said that state funding was tied to enrollment.

“As enrollment declines, so do our resources. While we have been having the ongoing conversation about right-sizing our staff to match these enrollment declines, including the attrition of seven positions coming into the current school year, with no allowable revenue increases, even that right-sizing can’t keep up with the fast decline of our operational resources and increasing expenses,” he said.

Demerath next pointed to a slide titled: “State Budget Impact,” which, he said, illustrated the impact to the district’s budget when the state, over the course of its biennial budget, does not allow revenue increases, and inflation rates, illustrated using the Consumer Price Index (CPI), continue to climb.”

Said Demerath: “The state CPI increases are directly linked to employee compensation as under state law a certified bargaining unit can only negotiate wage increases up to CPI.

“We’ve also made an effort to align our compensation increases with that CPI increase to ensure we can attract and retain quality 1Fort team members by allowing our compensation to keep up with increasing prices and remain competitive.”

Demerath pointed to a series of red arrows within a graph, which, he said, indicated the gap between CPI and the effects of no allowable revenue increase as dictated by the state.

“Over the course of this two-year state budget, the CPI has increased 5.93% with no allowable revenue increase. Just last week it was determined that CPI for ’23-’24 will be 8.01%,” he said.

“A much larger increase from the state would be needed to make any significant positive changes to this projection,” he said, adding that even as the state was “sitting on a nearly $7 billion surplus,” we’re hopeful, but it’s hard to be too optimistic about what funding might come to public schools in the next state budget.”

A slide indicted the history of per pupil aid over a 19-year period as granted by the state.

“As you can see, only once in the last 14 years the per pupil increase granted by the state exceeded $200. So we are hopeful, but not necessarily optimistic about the state funding us with the nearly $7 billion surplus they have right now,” Demerath said.

Demerath noted the impact of the loss of the one-time federal COVID Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds.

“This was meant to fill the gap left by the lack of state funding, which is what we decided to use it for,” he said, adding that in that year’s school budget, the district had included $1.15 million in ESSER funds to help offset the lack of state funding.

“We have one more year of about $750,000 of this funding available, and then it disappears, adding to the fiscal cliff we’re facing,” Demerath said.

Demerath said that the unsuccessful operational referendum in November, 2022, had provided the district with an opportunity to learn.

Among lessons, he said, the district learned that the complicated nature of the referendum question may have been a contributing factor to its failure to pass. The district learned that a next operational referendum question should be simplified, he said.

Additionally, two referendum questions on a single ballot added to the complexity, he said, noting that in April, the district would bring one question with one focus.

Further, he said, “the board had a conversation last month that pointed toward the desire to see more recurring funding as part of any solution, and that having more recurring funding would provide some future financial stability, although the board was unsure exactly how that might look and what it might mean for the ballot question.”

The board’s indication that it wanted to consider a question with more recurring funding prompted the creation of two proposed referendum options, Demerath said.

Pointing to a slide, Demerath said the district’s intension would be to “continue a stable tax rate over the course of this referendum.”

A black line on the graph, he said, represented the district’s intention, while the red line illustrating a projected tax rate under both scenarios.

While the line indicated that overall the tax rate would decrease, Demerath said it also showed some “turbulence,” which, he noted, “would be smoothed out as we set the final capital debt structure for the $22 million capital referendum that was successful in November. So in the end it may look like a gradual decline.”

According to Demerath, the outcome indicated by the graph could be achieved by a board decision to potentially prepay capital debt, as economic circumstances might allow, each year over the course of the next four years.

While Demerath stated that both options requested the same total amount of $8 million collected over the same four-year period of the nonrecurring component, neither would result in a “permanent fix.”

“Unless funding mechanisms change at the state level, and get to a place where annual allowable revenue increases are aligned with annual inflationary expense increases, the district will continue to have to come back to the electorate with an operational referendum,” he said.

He added: “Both can be achieved using the same tax rate for the next four years. Tax rate stability is achieved through debt management.”

Would the operational referendum question posed in April, 2023, fail, Demerath said: “Our next opportunity for an operational referendum will not be until next spring (April 2024). Without this proposed referendum, it’s estimated that next year’s deficit will be approximately $6.8 million.”

In April, 2023, the measure failed by a margin of 950 votes, with 3,463 voters across the district casting ‘no’ votes and 2,513 voters deciding in favor of the question.

Following the failure of the referendum question posed in 2023, in April, the school board held a special meeting during which the district’s administrative team advised the board that its best solution to resolve the $6.8 million deficit was to initiate a process that would likely result in a number of preliminary notices of non-renewal delivered to some members of the district’s staff.

Also in April, 2023, board members reviewed “takeaways” from the voters’ reaction to the referendum, noting that the previous ask, made during the previous November, failed by a margin of 6.6% while the referendum requested in April failed by a margin of 15.9%.

“Given that our financial needs are not going away, and we do not have faith that our Legislature will adequately fund public education in the upcoming biennial budget, a need to seek another operational referendum is a known,” Demerath said, adding that state statutes regulate some of the logistics surrounding a school district’s ability to bring a referendum question before voters. Among them, he said, was a provision stipulating that districts only can place referendum questions on the ballots of regularly scheduled elections and may only ask two referendum questions within one calendar year.”

He added that the district’s next opportunity to place an operational referendum on a ballot would be February 2024, followed by April, 2024, and November 2024. Further, he said, while three election dates exist in 2024, the district would only be able to consider two ballots, citing the opportunity in the spring, and potentially again in the fall.

An earlier story about placement of and need for an $8 million referendum in 2023 is here: https://fortatkinsononline.com/fort-school-district-to-place-two-part-8-million-operational-referendum-on-april-ballot/.

In April, 2023, Demerath talked about the size of the district’s deficit, noting that projections developed in advance of the referendum showed that, would the referendum fail, the district would be looking to address a $6.8 million gap.

“Knowing the deficit we were facing, we knew that along with the referendum question we still had to right-size our staff to our declining enrollment and make cuts to get through the four years of the referendum that was proposed. So alongside running the referendum campaign, we were also working to fulfill that promise to the community,” Demerath said.

Demerath next talked about strategies used by the district to reduce its deficit, noting among them: “right-sizing our staff to align to current and forecasted enrollment and program needs, evaluation of all vacancies for possible attrition or restructuring, analysis of current programming to prioritize return on investment and recognize opportunities for strategic abandonment.

“These are the ones that we focused on in working to fulfill the promise to the community, making cuts alongside the referendum,” he added.

Demerath said, in April of 2023, that the district began making budgetary cuts a year ago as it prepared to bring an operational referendum before the voters.

Through attrition and restructuring, $539,652 was saved by leaving unfilled several positions, including those of one full-time elementary classroom teacher, one full-time math interventionist, one full-time high school math teacher, one full-time high school technology education teacher, one full-time middle school technology education teacher, one full-time middle school librarian and one full-time library support person.

“As the board considered referendum options, we knew that to make it through the four years of an operational referendum, we would have to come up with the cumulative total of $5 million in cuts through attrition, strategic abandonment or new revenue from the state,” Demerath said, adding that a strategy used by the district to close the funding gap included offering a retirement incentive to certified and support staff to allow for positions to be removed through attrition, rather than having to lay people off.

“This is the work we have been doing since January (2023),” he said.

Demerath said some 15 positions through retirements and resignations, would be cut by attrition for the 2023-24 school year, saving some $1.2 million.

Positions that were left unfilled included those of a special education teacher, elementary teacher, high school Spanish teacher, middle school physical education teacher, middle school English teacher, elementary school art teacher, a director of communications position, an elementary school librarian, a high school tech ed teacher, a high school math teacher, a high school counselor position, a middle school math teacher, a middle school math intervention coach, and paraprofessionals.

Additionally, he said: “through the $1.2 million in cuts as well as negotiated health insurance renewal that was lower than what was projected, we decreased the projected deficit for next year by over $1.4 million.”

Demerath next subtracted the $1.4 million is savings from the earlier predicted $6.8 million deficit to arrive at a new deficit amount of $5.4 million for which, he said, a set of strategies would need to be developed.

Also addressing the board last April, Abbott said that when employing an option, the administrative team will engage several strategies, including: “providing a competitive compensation and benefit package for 2023-24 and in our financial forecasting, right-sizing our staff to align to current forecasted enrollment and program needs, evaluation of all vacancies for possible attrition or restructuring, and analysis of current programming to prioritize return on investment and recognize opportunities for strategic abandonment.”

On April 24, 2023, responding to staffing reductions of approximately 45 positions districtwide, some 75 Fort Atkinson High School students staged a brief walkout to protest the loss of district staff. The students gathered outside of the school’s front entrance where they engaged in a moment of silence.

An earlier story about the student walkout is here: https://fortatkinsononline.com/fort-high-school-students-stage-walkout/.

In October, 2023, the board approved a reduction in the district’s mill rate for the 2023-24 school year.

Information shared through a release by the district called the decrease in the mill rate “historic,” further noting that it will be “the lowest the rate has been since 2008.”

As noted within the release, “the 2023-2024 approved mill rate of $9.61 per $1,000 of equalized assessed property value is down about 12% from last year’s mill rate of $10.95. The owner of a $200,000 home would pay about $1,922 in school taxes, from last year’s total of $2,190, depending on municipality. However, with the recent increase in the assessed values of many homes, an individual homeowner’s net reduction may vary.”

Additionally, the release noted: “The total school levy for the 2023-24 school year is $21,434,310, including $12,339,760 for the general fund, $8,900,000 in referendum debt, and $194,550 in non-referendum debt.”

Further, the release stated, “private school vouchers account for $1,699,858 of the district’s operating expenses, or 7.9% of the district’s total tax levy.”

“We are pleased that we have been able to present a budget to our community that includes a historic decrease in the mill rate for property owners. While this is positive news, our district also faces longterm financial challenges that will continue to have an impact on our students, staff, and families. We remain committed to making the most of the funds available to us and ensuring the sound financial management of our school district,” Abbott was quoted as saying in the release.

Due largely to the state of Wisconsin’s school funding formula and limited aid to schools over the past several years, the School District of Fort Atkinson is facing looming budget shortfalls. In spring 2023, several staff positions were reduced through attrition, resignations, retirements, and non-renewals for the 2023-24 school year, the release continued.

The board of education is exploring a potential operational referendum to appear on the ballot in the spring of 2024 to help address the challenges, the release read.

An earlier story offering information released by the district is here: https://fortatkinsononline.com/school-district-property-owners-to-see-12-reduction-in-mill-rate-compared-to-last-year/.

A lawn sign in support of a three-year, $6.5 million operational referendum proposed by the School District of Fort Atkinson stands in a yard near Luther Elementary School. District residents have voted down operational referendums proposed by the district in 2022 and 2023. The district’s most recent ask will appear on the April 2 spring general election ballot. Kim McDarison photo.

This post has already been read 2230 times!